Making smarter choices under certainty, risk, and uncertainty in a changing world

Uncertainty is all around us, never more so than today. Whether it concerns a global pandemic, the economy, or your finances, health, and relationships, much of what lies ahead in life remains uncertain.

Nonetheless, life continues. You still must earn a living, take care of the family, house, and car, and walk the dog. All under these new clouds of stress and uncertainty.

Faced with an important decision, levels of uncertainty play a tremendous role. This is where making smart choices is a key skill for personal and professional success. Leaders know that making good, fast decisions can be very challenging under the best of circumstances where facts and knowledge are constantly changing and decaying, and where there are more unknowns and uncertainties than knowns and certainties.

Applying effective strategies and techniques can help you improve your decision-making skills and improve your outcomes and success. You need valuable knowledge, as opposed to any data or information, for making quality decisions. It is not about having more information but having the right amount of valuable knowledge (and wisdom) that is available at the time of decision-making.

In this article, I will explain how you can make smarter choices under certainty, risk, and uncertainty in a changing world.

The two dimensions of decision-making

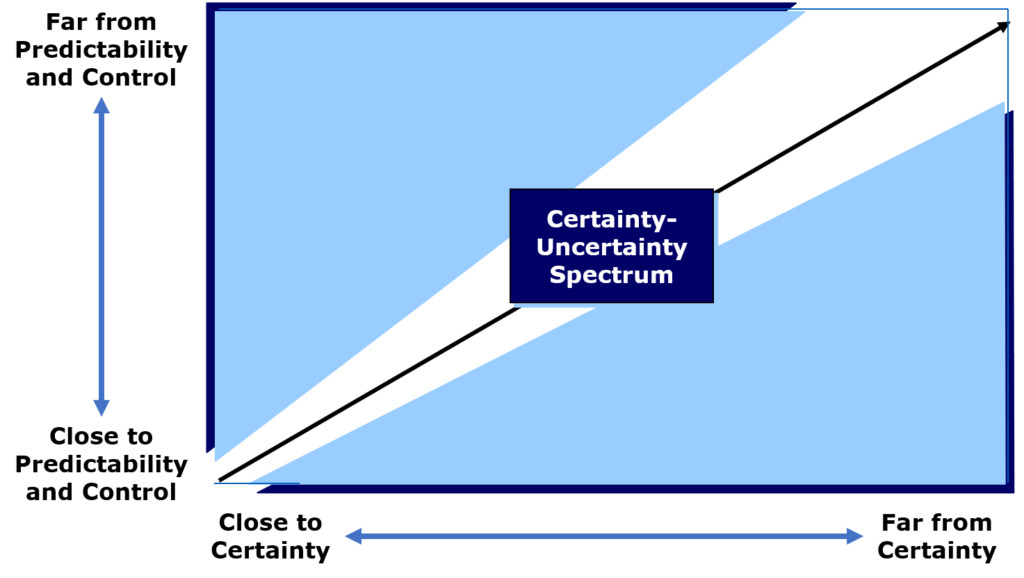

The two relevant dimensions for decision-making under certainty, risk, and uncertainty that form the certainty-uncertainty spectrum are:

- Degree of certainty – It ranges from close to certainty to far from certainty.

- Level of predictability and control – It moves from close to predictability and control to far from predictability and control.

Close to certainty

Decisions are close to certainty when ALL relevant information is known and when the cause and effect linkages are also known.

Extrapolating from experience is a good method to plan for future outcomes with a good degree of certainty in this close to certainty range.

Extra data or information can make our planning ‘perfect’. This is usually the case when a very similar issue or decision has been made in the past. Big data, analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence can significantly enhance our decision-making quality.

In this close to certainty range, you can plan with confidence using evidence-based decision-making, rational decision-making, traditional corporate planning, or even ‘follow the science’ methods.

When you can plan with certainty, or when forecasting and analysis can be performed with accuracy, you can make things operate with optimum efficiency. Efficiency is powerful with any work or system that can be standardized, measured, and predicted. It can be further enhanced and streamlined with technology, quality improvement, or business process re-engineering methods.

Far from certainty

At the other end of the certainty continuum, decisions are far from certainty when NO relevant information is known and when cause and effect linkages are unknown.

Extrapolating from experience is not a good method to predict future outcomes in this far from certainty range.

Extra data or information will not make our predictions perfect or better. Big data, analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence will only obscure our decision-making flaws.

In this far from certainty range, you cannot plan with any degree of confidence and certainty. The traditional methods of planning are very insufficient in these contexts.

Instead, you can only prepare for uncertainties to may occur through response, resilience, or business continuity planning. You cannot plan for uncertainties.

Trying to standardize, measure, and predict work that is far from certainty may only instill the illusion of control. It can demotivate people whose skill sets can meet unpredictable or uncontrollable demands. It can also rob people of their agility and capacity to adapt and respond rapidly with creativity and commitment.

Close to predictability and control

In close systems where patterns of causes and effects are repeated in predictable ways, they can be further streamlined and controlled for optimized efficiency. This frequently occurs in liner systems and sequential processing.

Your knowledge is constant with very few changes. The available information to improve efficiency is knowable and predictable. The situation is controllable and you can do something about it.

For example, the manufacturing process at a food processing facility. There are lots of moving components, many interconnecting parts or elements, and many people involved in the manufacturing process along the value chain. It’s easy to see the whole system and manage and control all the interconnecting parts with efficiency. The process is largely the same every day with few unforeseen situations likely to arise. This process can be effectively controlled and fully optimized for efficiency.

Far from predictability and control

At the other end of the predictability and control continuum are open systems where patterns of causes and effects cannot be determined in any predictable way. You must be agile and robust. Constantly, you must adapt rapidly and respond to uncertainties and the ever-changing world with creativity and commitment.

Flexibility and adaptability are more valuable than expertise and efficiency, as the most recent thing that happened may not or will not happen again. Your past is not the predictor for your future.

This occurs generally in non-linear and fluid systems. There are lots of different uncontrollable factors interacting with each other. They are not repeated in predictable or certain ways. It is extremely difficult to see the whole system at once because many known and unknown factors interact to create multiple reactions and outcomes.

You cannot manage or control the system and plan with confidence and certainty. You cannot do any accurate analysis, planning, or even forecasting beyond, say 100 to 150 days into the future, if at all. This makes planning, forecasting, or analysis extremely challenging.

As the future can change so quickly, you can only put in place contingencies to make the business more resilient when certainties do materializes.

The certainty-uncertainty spectrum is shown below.

Decision-making under certainty, uncertainty, and risk

Based on these two dimensions, there are three conditions along the certainty-uncertainty spectrum that you will face when making decisions under certainty, risk, and uncertainty.

Depending on the amount and degree of knowledge you must make smart choices, the conditions are:

- Making decisions under certainty (“I can acquire more reliable information”) – On one end of the certainty-uncertainty spectrum, you can acquire all available information and knowledge to reach a certain level of certainty and predictability. This will bring you closer to certainty and closer to predictability and control.

- Making decisions under pure uncertainty (“I don’t know. Let’s work it out together.”) – On the other end of the certainty-uncertainty spectrum, you are ignorant or have absolutely no knowledge, not even about the likelihood of occurrence for an event. Your behavior is purely based on your attitude towards the unknown. You are far from certainty and far from predictability and control. Acknowledging uncertainty and not knowing are the first step in getting closer to what is ‘certain’ or true.

- Making decisions under risk (“I know the probability estimates”) – Somewhere in-between the two ends of the certainty-uncertainty spectrum, you can acquire some information to improve your knowledge and help you decide and take action. You use the best available information to assign subjective probability and consequence estimates for the occurrence of each state. It may not be perfect, but it does the job.

Making decisions under certainty

On one end of the certainty-uncertainty spectrum, a condition of certainty exists when you know with reasonable certainty what the alternatives are, what conditions are associated with each alternative, and the outcome of each alternative.

Under conditions of certainty, accurate, measurable, and reliable information and knowledge on which you base your decisions are available to you. The cause-and-effect relationships are known. The future and outcome are highly predictable under conditions of certainty.

Such conditions exist in case of routine and repetitive decisions concerning the day-to-day operations of the business. This is the domain of best or good practices, where everyone knows how to operate. It’s just doing what everyone knows what and how to do. By planning and consulting with subject matter experts you will find several valid solutions.

Knowledge is constantly changing and decaying.

What we know is constantly adapting, changing, or renewing due to advances in science and technology. Everything experienced is new or will be new. Information growth has been and will be exponential.

Driven by the shorter and shorter half-life of information, much we know will decay very quickly. Hence, the need for continuous learning and updating. The problem is that we rarely consider the half-life of information. Even business models have half-lives!

Many people assume that whatever they learned in school remains true years or decades later. Medical students who learned in university that cells have 48 chromosomes would not learn later in life that this is wrong unless they made an effort to do so.

With the constant changing and decaying of facts, knowledge, and information, there will be more uncertainty than certainty and more unknowns than knowns.

Therefore, there’s not much value in doing a five-year plan for anything when living in uncertainty. If you are constantly revising your predictions, learning from mistakes, and become very good at planning and forecasting, probably the furthest out you can see is about one year.

Time horizons for planning and forecasting have been and will be severely compressed.

But for the rest of us who are not quite that rigorous, who don’t always review your forecasts, and see how right you are and how long you are and why then it’s more likely that the horizon for any ‘accurate’ forecasting is much less than 300 days.

Perhaps, we can only rely on the fast-and-frugal heuristics or rules-of-thumb in adaptive ways to make decisions under risk and uncertainty.

Making decisions under uncertainty

Even the simplest of decisions carry some level of uncertainty.

Conditions of uncertainty exist on the other end of the certainty-uncertainty spectrum when the future and outcome are unpredictable and uncontrollable. Everything is in a state of flux or change. You are not aware of available alternatives, the opportunities, and risks associated with each alternative, the likelihood and consequences of each alternative, and the likelihood and extent of your success.

In making decisions under pure uncertainty, you do not have information and knowledge about the future and outcomes.

There are more unknowns, than knowns. Nobody knows what will happen. There is no possibility of knowing what could occur in the future to alter the outcome of your decision.

You can only make assumptions and guestimates about the situation that provides a reasonable framework for decision-making. You depend on your judgment and intuition to make decisions.

When you admit that “I don’t know” and be open about it, you are less likely to fall into the trap of black-and-white thinking. Admission of uncertainty and what you don’t know can lead to a search for more information. You must first get comfortable with being uncomfortable. Then nudge yourself towards the close to certainty end of the certainty-uncertainty spectrum.

One way to do this is to view decisions made under uncertainty as changeable and reversible. Jeff Bezos of Amazon said that when a decision is reversible, you can make it fast and without perfect information or certainty.

View these changeable and reversible decisions as information that informs future decisions or improvements rather than viewing them as disastrous mistakes or failures.

Other strategies to respond to uncertainty or to reduce uncertainty include:

- Using scenarios to construct alternative narratives or stories that explore more possibilities and probabilities through constructive arguments, networking, collaboration, and cooperation; and information gathering and sharing. Jeff Bezos of Amazon considers 70% certainty to be the cut-off point where it is appropriate to decide. That means acting once you have 70% of the required information, instead of waiting longer. Deciding at 70% certainty and then course-correcting is a lot more effective than waiting for 90% certainty and losing the opportunity.

- Learning through rigorous experimentations and constant failures to uncover what you do know and what you don’t know. Often the best way to probe is to create experiments that are safe to fail and for gathering data. Use minimum viable products to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about your customers or stakeholders with the least amount of effort and potential failures.

Making decisions under risk

Risk implies a degree of uncertainty and an inability to fully control the outcomes or consequences of such an action.

When you have incomplete or some information about the opportunities and risks associated with each alternative, the likelihood and consequences of each alternative, and the likelihood and extent of your success, you are making decisions under a state of risk.

When making decisions under risk, you have some knowledge regarding the likelihood of occurrence of each outcome. When probability can be factored into your decision-making process when making decisions under risk, probability can be a substitute for certainty or complete knowledge.

In making decisions under risk, you can predict the likelihood of a future outcome. Risk means uncertainty for which the probability distribution is known. But when making decisions under uncertainty, the probability distribution is not known.

Decision-makers often lack information. Probability assessment reasonably quantifies this information gap between what is known and what needs to be known for an ‘optimal’ or ‘good’ decision. The probabilistic models and probability are used for protection against adverse uncertainty and exploitation of the unknown.

Risks can be managed while uncertainty is uncontrollable. You can assign a probability to risks events using methods like the ISO 31000 risk management process. While with uncertainty and unknowns, you can’t.

Calculable risk is present when future events occur with some measurable probability. Uncertainty is present when the likelihood of future events is indefinite or incalculable.

If you are certain of the occurrence (or non-occurrence) of an event, you use the probability of one (or zero). Therefore, when making decisions under certainty, a good decision is judged by the outcome alone.

However, if you are uncertain, you would say, “I really don’t know.” Decisions made under risk and uncertainty can only be judged by the quality of the decision-making at the time it is being made, not by the quality of the consequences after the outcome of the decision-making becomes known.

How you frame your situation or problem, either as uncertainty or risk, can make a significant difference to your conclusion and how you approach your decision-making.

| Being aware of the distinction between uncertainty and risk and applying this knowledge in scientific writings not only is of great importance for scientific coherence but also has meaningful practical implications for government and business because the rules used for decision-making under risk differ from those used for decision-making under uncertainty. As an example, Angner (2012) discusses the regulation of new and unstudied chemical substances. There is little hard data on them, but there is some probability that they will turn out to be toxic. If a policymaker would argue that the decision at hand concerns uncertainty, he or she would have to decide that the new chemical should be banned or heavily regulated until its safety can be established. Speaking in behavioral economic terms, either the minimax (minimizing the maximum amount of deaths) or the maximin (maximizing the minimum amount of profit) criterion applies in this situation. However, if the policymaker argues that one can and must assign probabilities to all outcomes, he or she faces a choice under risk, and will probably permit the use of the new chemical because the probability that it will turn out to be truly dangerous is low (the expected utility, the alternative with the greatest amount of utility, in the long run, is highest for permitting the use). This example shows that decision-making under uncertainty versus risk results in different responses. Therefore, whether a decision is treated as a choice under uncertainty or under risk can have real consequences. (Source: De Groot K and Thurik R (2018) Disentangling Risk and Uncertainty: When Risk-Taking Measures Are Not About Risk. Front. Psychol. 9:2194. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02194) |

Therefore, always strive to move from deciding under uncertainty to deciding under risk by assigning probabilities to outcomes.

Note that the main sources of errors in risky decision-making problems are false assumptions, not having an accurate estimation of the probabilities, relying on expectations, difficulties in measuring the utility function, and forecast errors. These are limitations when making decisions under risk.

For more information on how to plan and execute your strategy under risk, I have written about the nine key principles that relate to the rapid-cycle planning-and-execution approach.

Journalist, author, and podcaster Scott Young discussed a good model for making a decision under risk (uncertainty) that focuses on four distinct but related areas:

1. Do you even need to accept any additional risk?

If you can succeed without assuming more risk, then don’t accept any additional risk.

If, on the other hand, accepting added risk increases your chance or likelihood of success or creates opportunities that could offer a decisive advantage or value to you, then you should consider taking on that risk.

Put in place contingencies or mitigations to minimize your risk or maximize your opportunities.

2. What additional information do you need to decide?

If you’re going to make a risky decision, then you want to have the best available information possible before making that decision. You would like to use that information to improve your chance of success while reducing your chance of catastrophic failure.

While you won’t ever have perfect knowledge of the situation, get comfortable with some degree of ambiguity, uncertainty, or unknowns.

Based on your appetite for risk-taking (or opportunity-seeking), determine the percentage of certainty or percentage of information that will be your cut-off point to decide. For Jeff Bezos, it is 70% certainty.

3. What are your options if you achieve less-than-ideal results?

While you can only hope for the best, the associated risk might leave you short of your goal.

Understanding what that means and what follow-on actions could be necessary as part of your risk-taking action. There are varying degrees of success and failure. Be prepared for either one.

While you can think about the situation thoroughly, most decisions are changeable and reversible. Just decide, move on, and course correct. Don’t overthink or overcomplicate your decision. Indecision is also a decision.

4. What are the potential costs of accepting the risk?

If you meet with wild success, this is less of an issue.

But if things don’t go as planned, you might find yourself answering for your decisions. Do the benefits outweigh the risk? Or does the risk pose such a threat that you’re just gambling on success?

And, even if you’re successful, there may be consequences to your decision.

You can plan under certainty, but you can only respond and be resilient under risk and uncertainty. Be prepared to constantly pivot or course correct as more information comes to light. Quickly experiment and learn from your ‘mistakes’.

Learn four things from Jeff Bezos’s approach to making decisions under risk and uncertainty:

- Focus on decision velocity to drive innovation. (Speed matters to your future success.)

- Make decisions with 70% of the information you wish you had. (Perfection kills; good enough succeeds.)

- Most decisions are easily changeable and reversible. (Don’t be paralyzed with indecision.)

- Disagree and commit to a decision and take immediate action. (Agree to disagree; move on with your decision.)

In summary, do not fear making decisions under risk and uncertainty. It doesn’t mean you have to avoid risk and uncertainty either. Consider them as opportunities to succeed instead.

Respect risk and uncertainty as they present themselves. Understand how to embrace and exploit them to your advantage.

As you lead and manage people and organizations, risk and uncertainty and the fear of the unknowns will always present themselves. So, get used to them.

Decide fast, move on to action, and course correct to succeed.