How to identify and manage uncertainties for an unpredictable future (and it’s not waiting and do nothing)

On 31 December 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) learned of several cases of severe pneumonia in the Chinese city of Wuhan. This strain of coronavirus has since spread through China and into other countries. WHO later named COVID-19.

The emergence of the coronavirus was exactly the type of fast-emerging risk with uncertain consequences that could have triggered quick actions by governments and organisations. Instead, it was played down or dismissed by many. They adopted a wait and see approach to risk management.

Better-prepared organisations and governments responded positively to news of minimal spread. They rapidly drafted contingencies before the situation deteriorated.

When the first reports of lockdowns came from China, most governments and organisations in the West had weeks to act on this emerging information. But they chose to wait and see. It was their approach to managing their risks. There wasn’t any instant action. No planning was immediately initiated in anticipation of its arrival.

Risk management by-passed

I know, because I have intimate knowledge of one such organisation. No one took notice in that organisation until the coronavirus appeared at its doorstep. Everyone scrambled for action subsequently. Emergency meetings were held to understand the situation. By then, it was already too late.

That organisation did have a risk management framework in place. Every year, it had certified that their risk management framework and processes have been working. That fact was published in their annual report. Risk management was working better on paper than in practice.

The coronavirus was not taken seriously by the senior management of that organisation. Eventually, it was forced to deal with it as an issue, not as an emerging risk!

It was re-active risk management.

From hindsight, this ‘wait and see’ approach to risk management has been proven fatal.

When the world did react seriously to the coronavirus spread, many governments and organisations were already lagging. There were no face mask, sanitisers and personal protective equipment (PPE) for sale in bulk quantities. There was a sudden surge in sales and demand.

In the meantime, healthcare and essential workers were exposed to the coronavirus without PPE.

Economies went into lockdown just to buy time to get these stock in place and to plan for next steps. The economic price paid has been enormous for poor risk management.

Coronavirus is not a “black swan” event

Nassim Taleb coined the term “black swan” to describe an event that is rare, unpredictable. It has an extreme impact.

According to Taleb, coronavirus isn’t one of those black swan events.

He says it’s a white swan because it has been predicted and not rare at all. Take the long list of epidemics that occurred over the last couple of decades — Ebola, SARS, MERS and Zika.

All these should have woken leaders up to the inevitability of this coronavirus crisis. The likelihood of a pandemic occurring is high.

In other words, we were warned.

It is easy to be complacent or dismissive

During the first lockdown, many locations had experienced lower rates of coronavirus infection. The curve had been flattened. Success was on the cards.

Then complacency set in.

Many assumed that the worst had passed. Life would get back to normal again. People dismissed the emergence of the second, third, etc. waves even when there is no vaccine to come for many months.

The first lockdown was supposed to buy time for more preventive and proactive actions to be taken. It was meant to ramp up planning for the inevitable future waves of coronavirus to come.

I was told that some organisations wound back their planned actions after the first wave. When they saw that the coronavirus curve had flattened, there was no longer any urgency to act. Life for some went back to ‘normal’.

Then the second wave came. People were caught off guard. Many then realised the seriousness of the coronavirus.

Many governments and organisations started to take things seriously. By then, it was too late.

Is this how risk management is supposed to be — reactive to circumstances?

Four levels of residual uncertainty

Let us dig deeper.

The level of uncertain is based on the “best available information”. This is one of the principles of effective risk management in ISO 31000:2018 Risk management — Guidelines. Risk management explicitly takes into account any limitations and uncertainties associated with such information and expectations.

The best available information at that time could have helped us identify clear trends or expectations about coronavirus. When the right analysis was performed, many factors that were unknown were known.

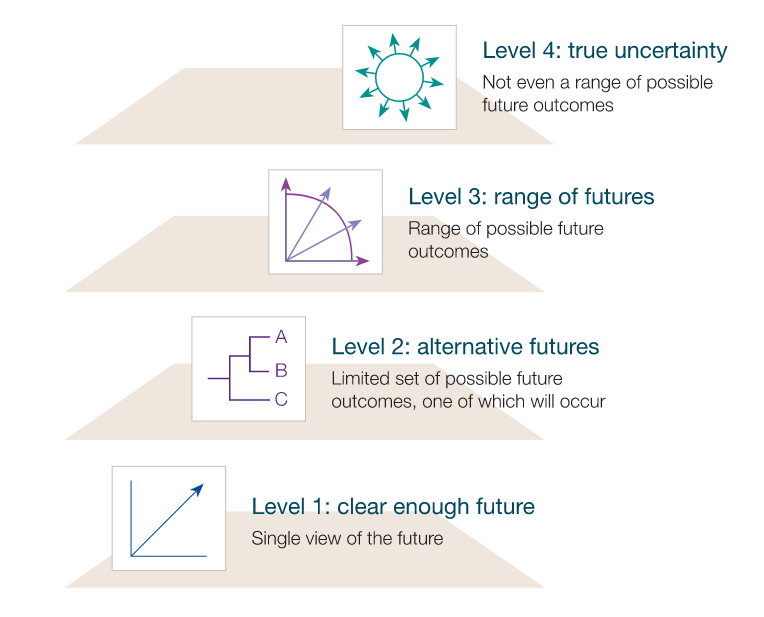

The uncertainty that remains after the best possible analysis using the best available information is residual uncertainty. It falls into one of four broad levels as shown below. (McKinsey, 2000)

- Level one: A clear enough future — Managers can develop a single forecast that is sufficiently precise.

- Level two: Alternative futures — Analysis can’t identify which outcome will come to pass. The possible outcomes are discrete and clear. But it is difficult to predict which will occur. Getting information that helps establish the relative probabilities of the alternative outcomes should be a high priority.

- Level three: A range of futures — The best analysis may identify only a broad range of potential outcomes. The possible outcomes are not discrete and clear.

- Level four: True ambiguity — Some dimensions of uncertainty interact to create an environment that is virtually impossible to predict or identify a range of potential outcomes. Analysis at this level is highly qualitative. Level four situations are rare. But they do exist.

When information about the coronavirus started to emerge in December 2019, the uncertainty level moved from Level Three to Level Two in January 2020.

Some may argue that it could also be a Level One uncertainty when lockdowns in Wuhan started. But that depends on your risk appetite and perspective of things.

Risk management needs to be proactive

Risk management as a device for increasing certainty and creating value. It should be considered as a means for achieving ever more positive outcomes.

The coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated one key thing — many organisations (and governments) paid lip service to risk management.

Risk management has become a tick-the-box activity for many organisations. More so, during periods of economic growth. But they reacted differently to pandemics or downside uncertainties.

The use of risk registers has also been a ‘tick-box’ exercise. It has been characterised as compliance.

The coronavirus pandemic has clearly shown the need for greater attention and rigour in identifying, escalating and managing uncertainties or emerging risks.

The formulaic approach to risk management has been entrenched in many organisations. Complicated flowcharts and in-depth risk policies and framework documents are often difficult and time-consuming to follow. Over-engineered templates and processes plague many risk management frameworks.

An effective risk management process helps us with decisive decision-making and quick action-taken. It has to be effective in identifying, escalating and managing fast-emerging, high impact uncertainties.

This will require the following actions:

- Develop people to become effective risk-takers. There are great opportunities to learn regardless of the situation — good and bad. Equip and develop your workforce to make better decisions and take risks.

- Create a positive operating environment for employees to be actively engaged at work. Engaged employees are highly involved in and enthusiastic about their work and workplace. They make better decisions and take risks for a better outcome — including acting on uncertainties and threats.

- Empower and encourage your workforce to raise issues and risks without fear or favour. Issues are known events. Risks are known uncertainties. Known issues must be actioned in priority over risks especially when their impact can be high or severe.

- Categorise risks as either emerging uncertainties (monitor and do nothing, for now) or strategic risks (action required now) after separating them from known issues.

- Set clear escalation triggers and processes for escalating uncertainties. This occurs especially when uncertainties could threaten the achievement of strategic objectives.

- Identify low-cost, low-regret incremental actions that will drive conversations and decisive action-taking.

Emerging risks tend to be complex. They are often unpredictable. This will naturally lead to a variety of viewpoints and conflicting opinions.

The outcome is often an agreement to wait and see and revisit the problem next time. No concrete action is taken.

Engage your workforce to take risk

Gallup’s research showed that 71% of engaged employees strongly agreed they could take risks at work that could lead to important new products, services or solutions. Among actively disengaged employees, that number drops to a miserly 2%.

Their research showed that engaged employees are 36 times more likely to take the kind of risks that can lead to breakthroughs and positive results.

In other words, a high number of disengaged employees puts organisations at risk of serious decision-making mistakes. That includes doing something that should not have been done and doing nothing. These disengaged employees will likely ignore or overlook key emerging risks like coronavirus.

According to Gallup’s meta-analysis, organisations with a highly engaged workforce scored 17% higher on productivity.

Unfortunately, Gallup also found that 85% of employees are not engaged in workplaces.

Disengaged employees will subsequently put their organisation at risk. And they themselves have become a risk or liability to their employers.

That said, risk-taking can be less risky than risk-aversion!

The science of taking micro-steps

Let us look at the science of taking micro-steps before proceeding further.

BJ Fogg, an academic at Stanford and the creator of TinyHabits.com, has focused deeply on how to change human behaviour.

One of his most powerful contributions is a simple solution to how we can

stop sabotaging our own best efforts to build new habits. He found that as soon as we think about creating a habit, our brains immediately find ways to ‘sabotage’ our well-meaning plans.

For example, going for a run in the morning. It doesn’t take much, as you are lying in your warm bed, to think of all those excellent reasons why you can’t go for that run today.

Fogg says that the secret to changing human behaviour is to define the first step that takes less than sixty seconds to do.

This aligns strongly with David Allen’s insight. David is the productivity guru at Getting Things Done. He says that you can’t do projects. Instead, you can only do “the next action.”

The works of Fogg and Allen tell us to define our next micro-step. Deconstruct the work into pieces and incrementally build it up to achieve the outcome we are seeking. Don’t overwhelm ourselves with analysis paralysis and inaction.

Incrementally build the habit of running in the morning by:

- Getting your running gear ready the night before.

- Putting on your running shoes as soon as you get out of bed.

- Walking around the house.

- Going for a short walk around the block.

- Running a short distance.

- Progress to longer runs overtime.

Identifying your next micro-steps for managing risks

This micro-step approach to risk management is supported by Gartner research. Gartner found that providing precise and detailed analysis of the uncertain situation has limited benefit. It can be like biting off a whole elephant all at once. Our brains are not wired to take in so much information and process it.

The key is to identify smaller subsets of an emerging risk that require some urgent action now. This overcomes the do-nothing, wait-and-see approach.

Success in managing uncertainties requires us to clearly define our next micro-step.

Focus on presenting low-cost, low-regret, low-risk incremental options and solutions that relate to small subsets of a larger emerging risk.

These micro-steps may require relatively little funding or disruption. The risk of failure is lessened by taking small steps.

The micro-steps for the emerging coronavirus risk:

- Find out more about the emerging cases of severe pneumonia in Wuhan.

- Determine the causes.

- Understand its potential impact on humans.

- Determine whether it could spread beyond Wuhan.

- Identify potential what-if scenarios if it does spread.

- Identify potential impacts on the organisation.

Asking for less encourages action-taking

Asking for less encourages decision-makers to take action. If the analysis is off or incorrect, the consequences will be relatively insignificant.

Focus on the small impacts first when managing fast-emerging risk. That will encourage action-taking. But time may be of the essence. So act quickly in small incremental steps.

Identifying small action steps avoids paralysis in decision-making and action-taking. It increases confidence in identifying and managing that uncertainty as it unfolds. It eliminates the ‘wait and see’ approach to risk management.

As more information is available and the uncertainty unfolds, people may eventually recognise that emerging risk as a strategic risk!

Other actions to enhance the management of uncertainties

Implement the following actions:

- Place risk in a positive context. Talk about opportunities as well as risks. Avoid using words such as “risk” if they have a negative meaning in your organisation. Consider alternatives such as ‘volatility’ and ‘uncertainty’.

- Integrate your strategy and risk decisions. Consider the potential for better or worse-than-expected outcomes from the outset.

- Management should adopt the 25:75 rule. Spend 25% of the executive team meetings looking outwards and forwards. This will help executives identify external and future threats and opportunities. Spend the remaining 75% of executive meetings looking inwards and backwards.

- All executive meeting papers should have a dedicated risk section. It highlights any opportunities and risks associated with the achievement of the organisation’s strategic objectives. This provides visible anchor points for discussion of the strategic risk-reward equation.

Finally, to manage fast-emerging risks …

There are ways to get around procrastination and inaction.

Therefore, to manage fast-emerging uncertainties:

- Empower your engaged employees to take risks.

- Identify your micro-steps.

- Ask for less to encourage action-taking.

- Focus on opportunities.

Uncertainties will become more common in an unpredictable world that we live in. Therefore, plan for them.