PrOACT 31000 – Your practical guide for making better-informed decisions under uncertainty

Making decisions is a fundamental life skill for everyone.

Solving problems and making good decisions are two most important determinants of how well you meet your responsibilities and achieve your personal and professional goals.

The good news is that you can learn to make better decisions.

As I like simplicity and common sense, the PrOACT approach (outlined in the book Smart Choices) is by far the best structured but simple framework for decision making and problem-solving that I have seen. It helps you see both the tangible and intangible aspects of your situation more clearly and to translate all pertinent facts, feelings, opinions, beliefs and advice into the best possible decision.

‘PrOACT’ is a mnemonic that stands for five key “elements of smart choices”:

- Problem statement

- Objectives

- Alternatives

- Consequences

- Trade-offs

The remaining three “elements of smart choices” (URL) help clarify decisions in volatile or evolving environments.

- Uncertainty

- Risk tolerance

- Linked decisions

Some decisions won’t involve these additional three elements, but many of your most important decisions will as we are living in uncertainty and challenging times.

Another reason why I like the PrOACT decision-making framework is that it can seamlessly accommodate the activities of the international risk management standard, ISO 31000, into any decision-making process that you are undertaking.

The incorporation of the ISO 31000 international risk management process into the world-class PrOACT decision-making framework has led to the creation of PrOACT 31000. It is a structured decision-making process that helps individuals and organisations make better-informed decisions under uncertainty.

What makes a good quality decision is the process by which informed decisions are made under uncertainty, not the ultimate outcome of the decision. You can fully control your decision-making process, but you cannot control the future outcome, good or bad, of your decision especially in the face of uncertainty.

A systematic process can help in making better decisions by helping to avoid or adjust for some of the biases in our thinking. While not all decisions are rational and systematic, there is great power in employing a systematic approach to decision making when there is great complexity or there are serious consequences of the decision. A rigorous process can help to shine a light on the complexity and keep you from stumbling through the fog.

The PrOACT 31000 decision-making process is a world-class way of making better-informed decisions under uncertainty. The structured process for making quality informed decisions consists of the following elements or activities:

- Find the right problem to start with.

- Identify your real objectives.

- Create a range of alternatives tailored to your problem and objectives.

- Understand the consequences each alternative would have for each of your objectives.

- Make trade-offs among conflicting objectives.

- Review your problem definition, objectives, alternatives and consequences.

- Note – This is an additional “element of smart choices” that is not listed in the original PrOACT approach. I feel that this additional element is important from feedback and an improvement perspective. It also helps you improve your decisions and decision-making process.

- Identify opportunities and uncertainties that may affect your decision and objectives.

- Take account of your risk-taking attitude.

- Plan for linked decisions over time.

How to make quality decisions?

In the face of uncertainty – upside or downside, you can only judge the quality of a decision at the time it is being made, not after the outcome becomes known. That means a good decision can have a good or bad outcome.

The most fundamental distinction in decision making is that between the quality of the decision and the quality of the outcome.

Therefore, what makes a decision good and of quality is the process by which informed decisions are made, not the ultimate or future outcome itself. You can fully control your decision-making process by which the decision was made, but you cannot control the future outcome, good or bad, of your decision especially in the face of uncertainty.

You can only make an informed decision based on the best available information that is available to you when you are making your decision.

Given that your decision-making process is vital for making quality decisions when you are faced with a problem and don’t know what steps to take, ask the following questions:

- Why do we have this problem?

- How do we solve this problem?

- What specific steps must we take to solve this problem?

Otherwise, you can use the PrOACT 31000 decision-making process listed in this page.

Ten questions to get your started

Here are ten diagnostic questions to get you started in making better informed decisions:

- What’s my decision problem?

- What, broadly, do I have to decide?

- What specific decisions do I have to make as a part of the broad decision I have to decide?

- What are my fundamental objectives?

- Have I asked “Why” enough times to get to my bedrock wants and needs?

- What are my alternatives?

- Can I think of more good ones?

- What are the consequences of each alternative in terms of the achievement of each of my objectives?

- Can any alternatives be safely eliminated?

- What are the trade-offs among my more important objectives?

- Where do conflicting objectives concern me the most?

- Do any uncertainties pose serious problems? If so, which ones?

- How do they impact the consequences?

- How much risk am I willing to take?

- How good and how bad are the various possible consequences?

- What are ways of reducing my risk?

- Have I thought ahead, planning out into the future?

- Can I reduce my uncertainties or increase my opportunities by gathering information?

- What are the potential gains and the costs in time, money, and effort?

- Is the decision obvious or clear at this point?

- What reservations do I have about deciding now?

- In what ways could the decision be improved by a modest amount of added time and effort?

- What should I be working on?

- If the decision isn’t obvious, what do the critical issues appear to be?

- What facts and opinions would make my job easier?

The PrOACT-R-URL elements provide a framework that can profoundly redirect your decision making, enriching your possibilities and increasing your chances of finding a satisfying solution.

Element 1 – Find the right problem to start with (What am I deciding and why?)

- How to define your decision problem to solve the right problem?

- It is useful to start off by asking what problem you are trying to solve exactly. You can make a well-considered, well-thought-out decision, but if you started from the wrong place, you won’t have made the smart choice, or even a good decision. A good solution to a well-posed decision problem is almost always a smarter choice than an excellent solution to a poorly posed one.

- The way you frame your decision at the outset can make all the difference. State your decision problems carefully, acknowledging their complexity. This will determine the alternatives you consider and the way you evaluate them. Posing the right problem drives everything else.

- Crafting a good problem definition takes time. Maintain your perspective. Be creative about your problem definition.

- Turn problems into opportunities. Create new opportunities before a problem even arises, where appropriate.

- Rarely does a decision exist in isolation. Thinking through the context or circumstances of a decision problem will help keep you on the right track.

- Questions to ask:

- What and why am I trying to decide?

- What is the question or situation that presents doubt, uncertainty, perplexity, or difficulty?

- How big is the problem (what is its scope)?

- What are the fundamental principles or elements of the problem?

- What triggered this decision? Why am I even considering it now? Why does it matter to me?

- How can I personalise the problem in terms of human stories to increase the likelihood and extent of my success?

- What are the key assumptions and constraints? What I know and don’t know?

- What is my decision-making deadline?

- What is the context of my problem?

- Why does this problem need to be addressed?

- Who needs to be involved and how?

- Break the problem down into its component pieces. For example, “What new house should we move to?” or “How can we find a home that fits our family’s needs?” which includes the possibility of renovating the current home.

- Thinking about problem definitions is a fuzzy thing. A few tips include:

- Ask what trigger caused you to consider the problem in the first place – Every decision problem has a trigger or initiating force. The trigger is a good place to start because it is your link to the essential problem. Consider moving outside your comfort zone.

- Question the constraints contained in your problem statement – Problem definitions usually include constraints that narrow the range of alternatives you consider.

- Understand what other decisions impinge on or hinge on this decision – Thinking through the context of a decision problem will help keep you on the right track and find the right alternative or solution.

- Develop a workable scope for your problem definition – An ideal solution for a problem that is too narrow could be a poor solution for a more broadly and accurately defined problem.

- Gain fresh insights or perspectives by asking others how they see the situation.

- Get some other perspectives to see your problem in a new light, perhaps revealing new opportunities or exposing unnecessary, self-imposed constraints.

- Communication and consultation with your internal and external stakeholders will be vital in any decision-making process.

- Depending on the nature of the problem, you might seek advice from a family member, a knowledgeable friend, an acquaintance who has faced a similar problem, or a professional in a relevant field.

- Chances to redefine your problem are opportunities that often lead to better decisions and outcomes.

- Get some other perspectives to see your problem in a new light, perhaps revealing new opportunities or exposing unnecessary, self-imposed constraints.

- Ten tips for problem formation:

- Start with a few problems.

- Focus on the big problem that matters most to you.

- Look at the problem as an opportunity.

- State the problem in a creative way.

- Assess what triggers the problem.

- Identify the essential elements of the problem.

- Look at the context and its impact on the problem.

- Get other people’s insight or perspective on the problem.

- Revisit the problem (formulation) from time to time.

- Key review question – Is the problem clearly stated in a form broad enough to challenge assumptions, get at the root of the issue, break down perceived constraints, identify and avoid unintended consequences and generate long-lasting solutions?

Element 2 – Identify your real objectives (What do I want?)

- How to clarify and specify what you are really trying to achieve with your decision?

- A decision is a means to an end. Ask yourself what you most want to accomplish. Give direction to your problem by assessing your objectives explicitly.

- Determine and which of your interests, values, concerns, fears, and aspirations are most relevant to achieving your goal.

- Thinking through your objectives will give direction to your decision making.

- Your fundamental objectives will depend on your decision problem.

- Avoid making an unbalanced decision by making sure you have identified all your objectives.

- Before deciding, first, think about what success looks like for you in your present context or circumstances.

- Depending on the decision, your objectives could reflect concerns for your family, your employer, your community and country,

- A decision is a means to an end. Ask yourself what you most want to accomplish. Give direction to your problem by assessing your objectives explicitly.

- Answering the following questions honestly, clearly, and fully puts you on track to making smart choices.

- What would make me happy?

- What do I really want or need?

- What are my hopes and goals?

- What do I most want to avoid?

- What would constitute a best-case scenario for my decision? For example, if you are choosing a new office, your list of objectives might be minimal commute time, low cost, lots of space and fully staffed administrative services.

- What are some things I can control?

- What decision criteria are desirable?

- What assumptions did I make when deciding on my real objectives? (Note – Assumptions that do not hold true can become a risk to your outcome.)

- “If you don’t know where you’re going, any route will get you there” is an old saying that holds true in decision making. Too often, decision-makers don’t take the time to specify their objectives clearly and fully. As a result, they fail to get to where they want to go. So, let your objectives be your guide where they:

- Form the basis for evaluating the alternatives open to you. This will be your decision criteria, which seeks to answer the question, “What do I want to achieve in my decision?”

- Your decision criteria will help you identify what’s important and valuable to you so that you can make a choice and achieve the outcome you want.

- Only fundamental objectives should be used to evaluate and compare alternatives, which will be encapsulated in the decision criteria.

- Help you determine what information to seek and analyse.

- Help you explain your choices to others.

- Determine a decision’s importance and, consequently, how much time and effort it deserves.

- Form the basis for evaluating the alternatives open to you. This will be your decision criteria, which seeks to answer the question, “What do I want to achieve in my decision?”

- Five key steps to determine your objectives:

- Step 1 – Write down ALL the concerns you hope to address through your decision. Describe as completely as you can everything that you could ever want from your decision. Here are some techniques:

- Compose a wishlist – What would make you happy?

- Think about the worst possible outcome – What you most wanted to avoid?

- Consider the decision’s impact on others – What do you wish for them?

- Ask people who have faced similar situations, what they considered when making their decision.

- Consider a great alternative – What is so good about it?

- Consider a terrible alternative – What makes it so bad?

- Think about how you would explain your decision to others – How would you justify your decision to others?

- Step 2 – Convert your concerns into succinct objectives using a short phrase consisting of a verb and an object, such as “Minimise costs” or “Mitigate environmental damage”.

- For more sophistication, your objectives could incorporate SMART characteristics. “SMART” acronym stands for “specific,” “measurable,” “attainable,” “relevant,” and “time-bound.”

- Step 3 – Separate ends from means to establish your fundamental objectives.

- Distinguish between objectives that are means to an end (having leather seats in your new car) and those that end in themselves (having a comfortable and attractive interior).

- Simply ask “Why?“. Keep asking it until you can’t go any further.

- Asking “Why?” will lead you to what you really care about your fundamental objectives, as opposed to your means objectives.

- Step 4 – Clarify what you mean by each objective.

- For each fundamental objective, ask “What do I really mean by this?” to clearly see the components of your objectives, which will lead to better understanding.

- Fundamental objectives – What you want to accomplish.

- Means objectives – The things you need to accomplish before you can realise your fundamental objectives.

- Clarifying the meaning of your objectives will help you achieve them.

- For each fundamental objective, ask “What do I really mean by this?” to clearly see the components of your objectives, which will lead to better understanding.

- Step 5 – Test your objectives to see if they capture your interests. Ask yourself if you would be comfortable living with the resulting choices. If not, you may have overlooked or misstated some objectives. Re-examine them.

- Step 1 – Write down ALL the concerns you hope to address through your decision. Describe as completely as you can everything that you could ever want from your decision. Here are some techniques:

- List all possibly relevant objectives to help you guide your decision. Include both quantitative and qualitative objectives. Identifying objectives is an art, but it’s an art you can practice systematically.

- Communication and consultation with stakeholders – If you have other stakeholders in the outcome you are seeking to achieve, involve them in the objective finding process.

- Ask other people if there are other objectives you should consider.

- Do your best to refine your objectives by asking “Why?” until they are an accurate reflection of what you truly care about in this decision.

Element 3 – Create a range of alternatives tailored to your problem and objectives (What can I do?)

- How to create a range of imaginative or better alternatives to choose from that are tailored to solve your fundamental problem or meet your objectives?

- Three important points should be kept in mind.

- You can never choose an alternative or opportunity you have not considered. Alternatives are the raw material of decision making.

- No matter how many alternatives you have, your chosen alternative can be no better than the best of the lot. The payoff from seeking better, new or creative alternatives can be extremely high.

- Get rid of anything that is not going to move you closer to your ultimate or real objective.

- The greatest danger in formulating a decision problem is laziness. Make the effort and time to focus on generating or creating as many alternatives as possible.

- Spend the right amount of time to consider or create a few solid alternatives, supported by the appropriate amount of research and information.

- Don’t try to evaluate the alternatives just yet at the accumulating or brainstorming stage.

- Don’t box yourself in with limited alternatives. Too many decisions are made from an overly narrow, previously experienced, poorly constructed, incremental or default set of alternatives.

- Be aware that spending too much time considering all the alternatives can drive to overthinking and analysis paralysis. For each choice, you want to maximise the possible gain in the minimum amount of analysis time.

- Question your constraints – Most of the time, you can put assumed barriers around our options.

- For instance, if you were thinking about what laptop to buy, you can open up a lot more alternatives if you considered refurbished options or other solutions like using an iPad with a keyboard.

- Three important points should be kept in mind.

- Questions to ask:

- How can I achieve the objectives I’ve set? What are the best ways to achieve my decision outcome? (Do this separately for each individual objective, including both means objectives and fundamental objectives.)

- Who else can I consult with to get a different perspective?

- What are the possible choices that meet my decision criteria? Are they realistic? Have they been designed to address the objectives identified? Do they include creative solutions, challenging perceived constraints and combining elements in thoughtful ways that are practical?

- What are the constrains – real or assumed – that will prevent me from meeting my decision criteria and to achieve my objectives?

- What new solutions can be created from first principles? (Note – Create alternatives, not build on existing ones.)

- Here are some ways of generating alternatives:

- Ask the question, “How can I achieve this?”

- Break free from traditions, old mindsets and habits.

- Ask the question, “If everything was possible and there is nothing stopping me/us, I/we can ……”

- Learn from the past and from others or experimenting on new ideas, creations and opportunities.

- Do not judge the relevance of the alternatives too quickly. Create alternatives first, evaluate them later.

- Challenge constraints and assumptions.

- Set high aspirations and expectations.

- Do your own thinking first, then consult others.

- Don’t be afraid to ask others for suggestions or different perspectives.

- Give your subconscious time to operate.

- Never stop looking for alternatives.

Element 4 – Understand the consequences each alternative would have for each of your objectives (What do I know?)

- How to describe how well each alternative meets each of your objectives?

- Be sure you really understand the consequences of your alternatives before you make a choice. If you don’t, you surely will afterwards. You may not be very happy with them. Make full use of the best available information.

- To make a smart choice, compare the merits of the competing alternatives, assessing how well each satisfies your fundamental objectives, and how they meet (or don’t meet) your decision criteria.

- Layout the consequences each alternative would have against each of your objectives before you make a choice.

- If you describe the consequences well or clearly, your decision will often be obvious without requiring much further reflection. Note how you feel and what matters to you.

- Put yourself into the future and imagine that you are now living with one of your alternatives. Describe the consequences of each objective-linked alternative with appropriate accuracy, completeness, precision and honesty.

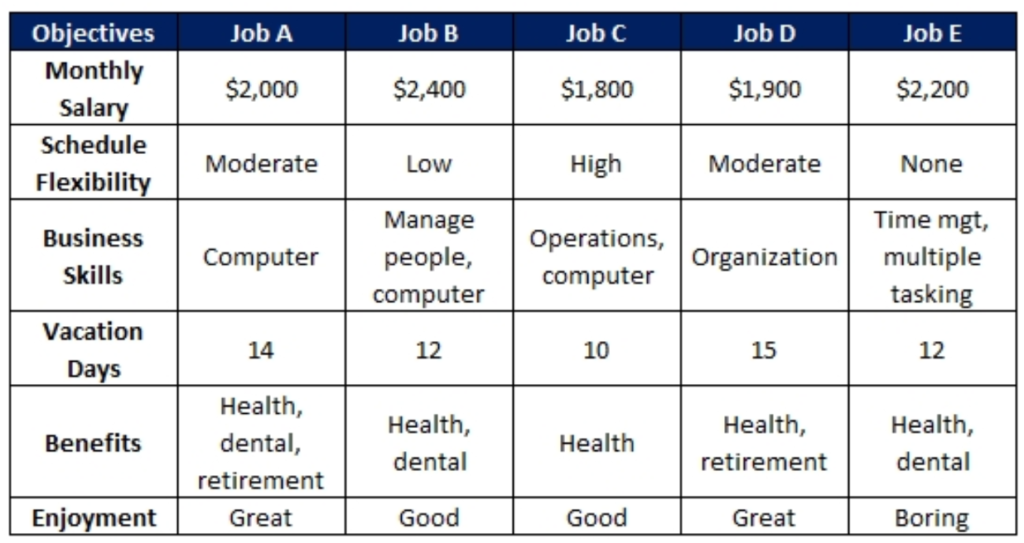

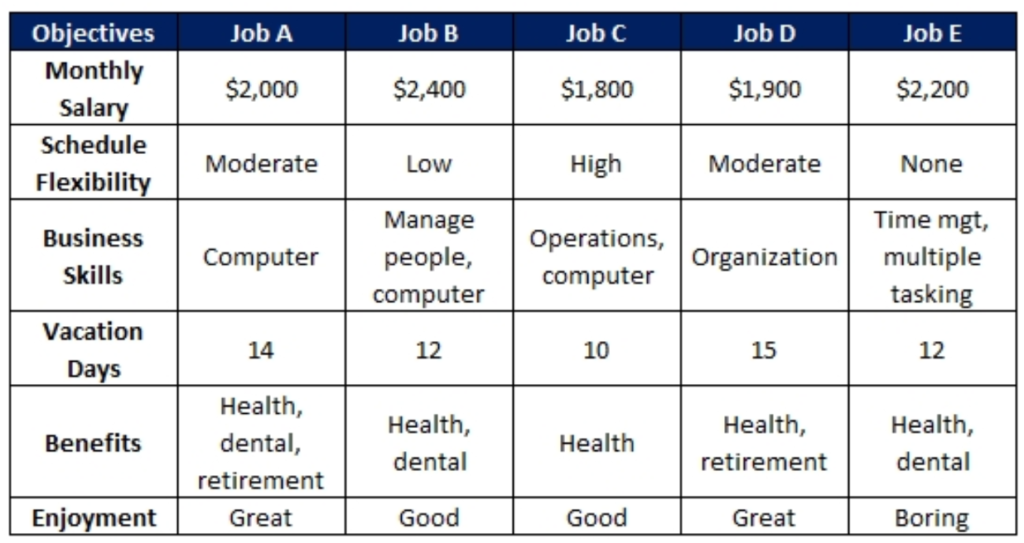

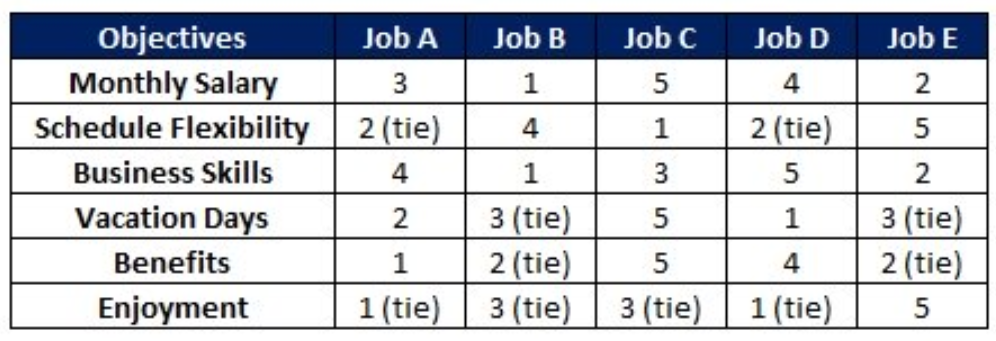

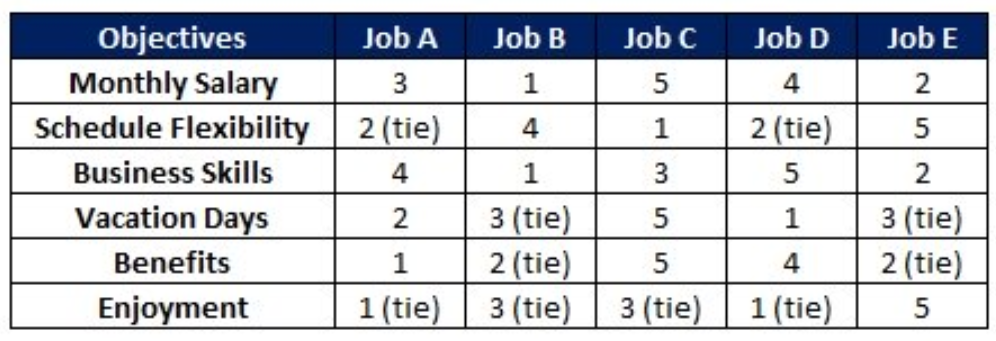

- Develop a consequences table (samples shown below) that puts a lot of information into a concise and orderly format. This allows you to easily compare your alternatives, objective by objective, in a systematic way.

- Identify meaningful categories that capture the essence of your objective.

- Construct a subjective or fit-for-purpose scale that directly measures your objective. Measures include dollars or percentages.

- Take your remaining alternatives and create a consequences table that displays how well each alternative stacks up against all your objectives.

- Quantify how well the alternative fulfils your objectives.

- Create a ranking system (sample ranking tables shown below) that reflects the range of possible outcomes that you could consider and decide.

- Find ways to try before you buy. Allow yourself to experience or experiment some of the consequences firsthand. Talk to experts or knowledgeable individuals who can help you understand potential consequences for complex areas.

- Recognise that some consequences can be uncertain and imprecise. This is perfectly okay.

- Questions to ask:

- Am I comfortable with the quality and amount of the information and level of analysis captured in the consequence table?

- Which options can I test or experiment to achieve the objectives or outcomes I am seeking?

- What evidence can I use to validate my decisions?

- What other factors could affect the alternatives and my decision?

Element 5 – Make trade-offs among conflicting objectives (What will I do?)

- How to make tough compromises when you can’t achieve all your objectives at once?

- The first step is to see if you can rule out some of your remaining alternatives before having to make tough trade-offs. The fewer the alternatives, the fewer the trade-offs you’ll need to make and the easier your decision will be.

- Decisions with multiple objectives cannot be resolved by focusing on any one objective.

- Making compromises or trade-offs is one of the most important and most difficult challenges in decision making.

- When decisions have conflicting or competing objectives, you need to give up one objective to achieve more in terms of another.

- The more alternatives you are considering and the more objectives you are pursuing, the more trade-offs and comprises you will need to make.

- Follow this simple rule – If alternative A is better than alternative B on some objectives and no worse than B on all other objectives, B can be eliminated from your consideration.

- Look at your consequence table and eliminate dominated alternatives.

- Working row by row that is, objective by objective, determine the consequence that best fulfils the objective and replace it with the number “1”. Then find the second-best consequence and replace it with the number “2” and so forth.

- If alternative A is equal or better than alternative B in every way, then you can say alternative A dominates alternative B. Eliminate alternative B because it has no chance of being the best option.

- Learn to embrace the possibility of failure. Fear of failure can paralyse your decision making.

- Make trade-off’s using even swaps – a technique suggested back in 1772 by Ben Franklin.

- Figure out whether you can ‘trade’ on one objective to get more of another. Use this knowledge to clarify your consequences.

- If all alternatives are rated equally for a given objective, then you can ignore that objective in choosing among those alternatives.

- After you have analysed your options and evaluate them against your decision criteria, it’s time to decide on the preferred alternative.

- A wrong decision is better than not making one. At least, you can learn from your mistakes and make better-informed decisions in the future. What all else fails, do something.

- Get up to 80% of the information you need. Then decide, take action and only look back to learn from it. Make your best decision and get on with it.

- NOT MAKING A DECISION IS A DECISION!

- Develop and implement your action plan to achieve the required outcome. Bring our plans to life!

- Questions to ask:

- Is there enough information on which to make a decision, or is it necessary to go back and revisit my problem, objectives and measures?

- Do the trade-offs suggest a new problem, objective or alternative?

- How much time do I have before my risk profile changes?

- What choices meet my decision criteria and can increase the likelihood and extent of my success?

- Do I have the capacity and capability to implement my decision in the best possible way after deciding?

- What could go wrong during implementation?

- What resources do I need?

- What assumptions have I made so far?

- What’s blocking me from making a decision? Why can’t I just decide now?

Element 6 – Review your problem definition, objectives, alternatives and consequences (How am I doing?)

- How to continuously check, recap, and reconsider your problem definition, objectives, alternatives and consequences?

- After deciding and implementing your actions to bring your decisions to life, this element has been added as a separate step to remind you that at any stage of the decision-making process, you need to check, recap, or reconsider your problem definition, objectives, alternatives and consequences. Be willing to stop, reassess, and reformulate your plan.

- Chances to redefine your problem are opportunities that often lead to better decisions and outcomes.

- From time to time as you work your way through the decision-making process, ask yourself, “Am I working on the right problem?”

- If you are not satisfied with the preferred choice and ranking, then you need to reconsider whether you have captured your decision problem adequately. The omission of an important objective can lead to an unsatisfactory result.

- When you have gained an understanding of your problem, you may identify additional objectives that you want to include in your decisions.

- Take time to reflect on the results of your decision-making process. This allows you to evaluate how your choice enabled your success.

- Consider what you would do differently in the future. Learn from any mistakes made to improve future decision making.

- Examine the outcomes achieved in order to make better decisions over time. Practice makes perfect.

- Troubleshoot your decision.

- Other factors to include and consider are uncertainties in the consequences, the level of risk you are willing to accept, and whether the decision is linked to others.

- Questions to ask:

- Am I working on the right problem? Was the problem adequately or clearly defined?

- Did I achieve my intended decision outcome? Was the solution effectively implemented?

- What can be done to increase the likelihood and extent of my success?

- Is my decision obvious now? If not, is it worth more effort, or should I just pick the best contender?

- What have I learned? How has my perception of the problem changed?

- How can I make better decisions in the future? What improvements can I make?

- What should I work on next?

Element 7 – Identify opportunities and uncertainties that may affect your decision and objectives (What opportunities and uncertainties impact my decision or objectives?)

- How to find, recognise and describe the opportunities and uncertainties that may affect your decision and achievement of your objectives?

- Life is full of uncertainties. Every decision carried risk – so, get used to it.

- The challenge for you is not to eliminate all surprises or risks, but to anticipate and prepare for them. To do that, you must acknowledge uncertainty, uncover it, recognise it, understand it and deal with it in an unbiased way. Systematically identify all the things that could cause a decision to fail or quantifying the change that those events will occur.

- You can raise the odds of making a good or informed decision in uncertain situations when you follow a structured decision-making process or framework like PrOACT 31000.

- Uncertainty adds a new layer of complexity to your decision-making or problem-solving. A single decision may involve many different opportunities and uncertainties, of varying levels of importance, and they may all interact, in tangled ways, to determine the ultimate consequences.

- The first step is to acknowledge the existence of opportunities and uncertainties in every decision. Think them through systematically. Take time to understand the various outcomes that might unfold, their likelihoods, and their consequences.

- Effective decision-making demands that you confront uncertainty – positive or negative, judging the likelihood of different outcomes and assessing their possible impacts. You can only reduce uncertainty as far as you can – thereafter, you have to manage it.

- Decisions made under uncertainty can only be judged by the quality of the decision making at the time it is being made, not by the quality of the consequences after the outcome of the decision-making becomes known.

- Whenever uncertainty exists, there can be no guarantee that a smart choice will lead to good consequences. That means a good decision can have a bad outcome. Or a bad decision can have a good outcome (aka luck).

- The most fundamental distinction in decision-making is that between the quality of the decision and the quality of the outcome.

- But over time, luck favours people who follow good decision-making procedures.

- While you can’t make uncertainty disappear, you can address it explicitly in our decision-making process.

- Questions to ask:

- What are the opportunities and uncertainties that may affect my decision?

- What could help or prevent me from achieving my objectives?

- What could go wrong with my decision? (Another way to think about negative uncertainty is to look for potential problems!)

- What are the possible outcomes of these uncertainties?

- What are the chances or likelihood of occurrence of each possible outcome?

- What are the consequences of each outcome?

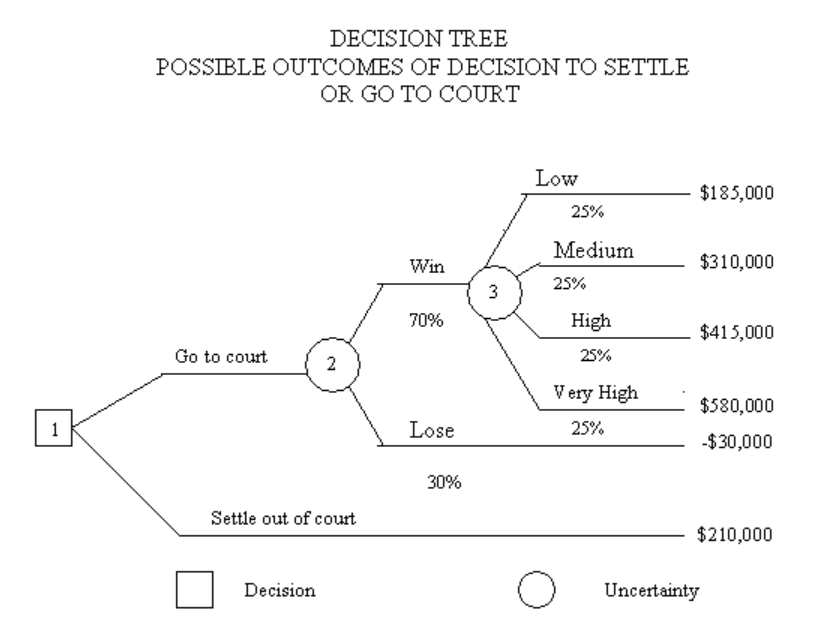

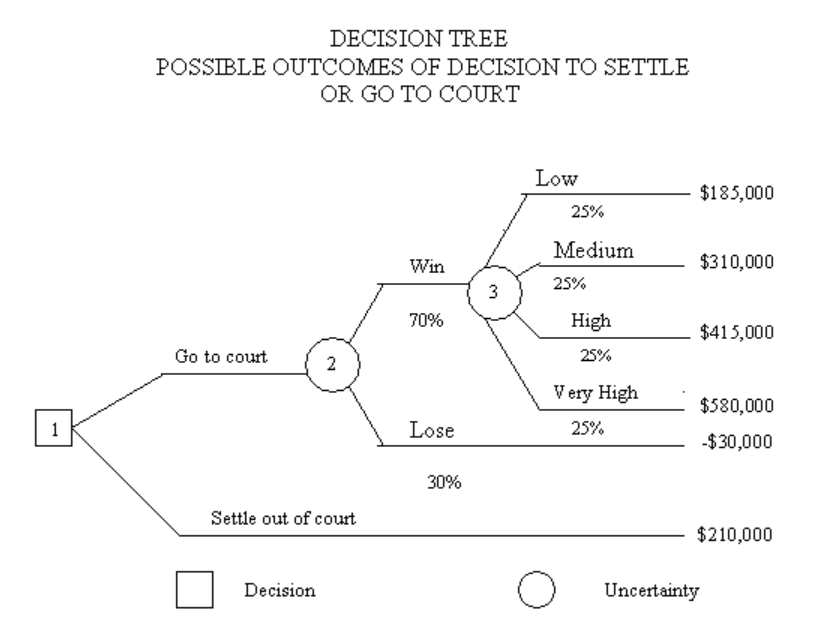

- Since most decisions involve consequences that are not totally knowable upfront, create a risk profile. Use risk profiles to simplify your decisions made under uncertainty. This provides a consistent basis for comparing the opportunities or uncertainties affecting each of your alternatives. Isolate its elements and evaluate them one by one.

- A risk profile captures the essential information about the way uncertainty affects an alternative. It describes the possible outcomes, their chances of occurring, and the associated consequences.

- The key is to capture the most critical uncertainties or opportunities (as there are potentially an infinite number to choose from) and provide best-guesses on chances of each outcome (which should be mutually exclusive).

- The international risk management standard, ISO 31000, could be used to identify, analyse, evaluate and treat any risk or known opportunities and uncertainties that may affect your decision and the achievement of your objectives.

- Risk identification is the activity of finding, recognising and describing opportunities and uncertainties. The key question to ask: “What could happen?“

- Risk analysis is the activity to comprehend the nature of the uncertainty, both positive or negative, and to determine the level of risk or risk rating using a decision or risk criteria.

- Risk evaluation is the activity of comparing the results of risk analysis with the risk criteria to determine whether the risk – opportunity or uncertainty – or its magnitude is acceptable or tolerable.

- Risk treatment is the activity of selecting and implementing options for addressing opportunities or uncertainties.

- Use the following steps to construct a risk profile:

- Identify the opportunities and uncertainties – List all known opportunities and uncertainties that might significantly influence the consequences of the alternative. Examine the uncertainties and eliminate those, which have a marginal impact.

- Define the outcomes – Specify the outcomes of each uncertainty – positive or negative – in terms of its impact on your decision and achievement of your objective.

- Assign chances or likelihood – This step involves a rating of the likelihood of the outcome occurring. This can be done quantitatively with a formal scale or through judgement either alone or with others using such techniques as nominal group technique.

- Portray the options and possibilities in a risk profile using tools like a decision tree (samples shown below).

Element 8 – Take account of your risk-taking attitude (What is my tolerance for risk-taking?

- How to understand your willingness to take risks in your quest for better decisions and the achievement of your objectives?

- Conscious awareness of your willingness to accept risk will make your decision-making process smoother and more effective. It will help you choose an alternative with the right level of risk that is suitable for you.

- Given the same uncertainties, different people would prefer different outcomes. Most people are moderately loss averse and would prefer to avoid bad outcomes, even if they have a shot at great outcomes.

- People take on some degree of risk knowing that it goes hand in hand with reward. You can either be risk-averse or a risk-taker, in any given situation.

- The basic principle – The more desirable the better consequences of a risk profile relative to the poorer consequences, the more willing you will be to take the risks necessary to get them.

- If you have a low tolerance for risk, you might want to consider alternatives that are more solid and predictable in making your decisions. Look carefully at the upside and downside and consider whether you can live with it.

- Questions to ask:

- What’s the worst that could happen to me?

- Am I fully committed to my decision?

- What am I willing to give up? Will this change my life for the better?

- What’s stopping me from taking a risk?

- Would I take a greater risk for a greater potential payoff or opportunity?

- Will taking the risk get me closer to what I really want?

- How can I plan to minimise the known risk?

- What happens if things don’t work out the way I want them to?

- Follow three simple steps:

- Think hard about the relative desirability of the consequences of the alternatives you are considering.

- Balance the desirability of the consequences with their chances of occurring.

- Choose the most attractive alternative.

- Ways where you can change the risk profile (usually making the worst-case scenario less bad):

- Share the risk with others (less upside, but also less downside).

- Seek risk-reducing information.

- Diversify the risk (similar to sharing risk).

- Hedge the risk (create ways where you might benefit a bit from the “bad thing” happening).

- Insure against risk (spend a small amount to prepare against big bad stuff).

Element 9 – Plan for linked decisions over time (How this decision can impact my future decisions?)

- How to plan by effectively coordinating current and future decisions through forward-thinking?

- Understanding how decisions are linked combined with a little foresight will help you make better choices.

- The essence of making smart linked decisions is planning.

- Think ahead and work backward in time. Continue working backward until you reach the individual alternatives for the basic decision.

- You will now have made a plan for each alternative so you will be able to evaluate it more clearly.

- What you decide today could influence your choices tomorrow.

- Your goals for tomorrow could be influenced by your choices made today. Therefore, many important decisions are linked over time.

- This may include unintended consequences – positive or negative – that may not be known now but could unfold later.

- Many important decision problems require you to select now (at the time of making the decision) among alternatives that will greatly influence your decisions in the future. There may be a connection between the current decision and one or more later ones.

- In such linked decisions, the alternative selected today creates the alternatives or opportunities available tomorrow. This affects the relative desirability of those future alternatives.

- But don’t look too far ahead as linked decisions can be years apart or they can be minutes apart.

- They may add a new layer of complexity to decision making.

- Make decisions in layers. With a series of interrelated decisions, start with the broadest one first, work down to the next level, then further down to a more detailed level.

- Questions to ask:

- Can my circumstances or perspective change especially with time?

- What new knowledge can enhance my understanding of the future outcome?

- What future decisions would naturally follow from each alternative in my decision?

- Do I need to make new decisions now, based on the best available information about the future?

- Do I need to develop flexible plans instead to keep my options open?

- There are six basic steps for analysing linked decisions:

- Understand the basic decision problem.

- Identify ways to reduce critical uncertainties.

- Identify future decisions linked to the basic decision.

- Understand relationships in linked decisions.

- Decide what to do in the basic decision.

- Treat later decisions as new decision problems.

Take control over your life

Create your own decision opportunities. Be proactive in your decision making. Look for new ways to formulate your decision problem. Search actively for hidden objectives, new alternatives, unacknowledged consequences, and appropriate tradeoffs.

Most importantly, be proactive in seeking decision opportunities that advance your long-range goals; your core values and beliefs; and the needs of your family, community, and employer. Take charge of your life by determining which decisions you will face and when you’ll face them.

Don’t just sit back and watch what good or bad comes your way.

Always find the right problem to solve

You can make a well-considered, well-thought-out decision.

But if you’ve started from the wrong place with the wrong decision problem you won’t have made the smart choice. The way you state your problem frames your decision. It determines the alternatives you consider and the way you evaluate them.

Posing the right problem drives everything else. Linking the problem explicitly to your objectives gives you the required guidance and direction.

Customise your approach

You may not need to use the PrOACT approach for every decision. Minor, routine decisions rarely warrant a full-blown analysis. Customise PrOACT-R-URL elements to your unique circumstances to make quality informed decisions.

Sometimes, the simple act of setting out your problem, objectives, alternatives, consequences, and tradeoffs, as well as any uncertainties, risks, or linked decision factors, will fully clarify the decision, pointing the way to the smart choice.

Beware of psychological traps

You must also avoid certain psychological traps that can derail your thinking. Psychologists have shown, for example, that the first ideas that come into our head when we start out to make a decision can have an undue impact on the ultimate choice we make.

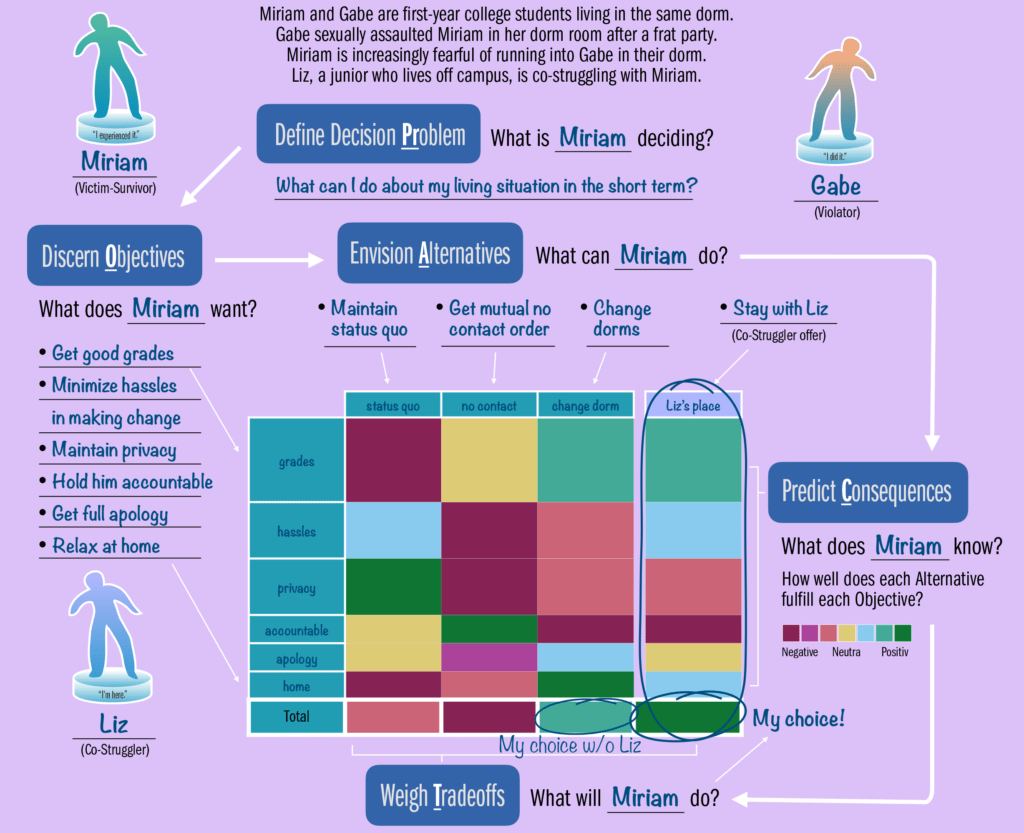

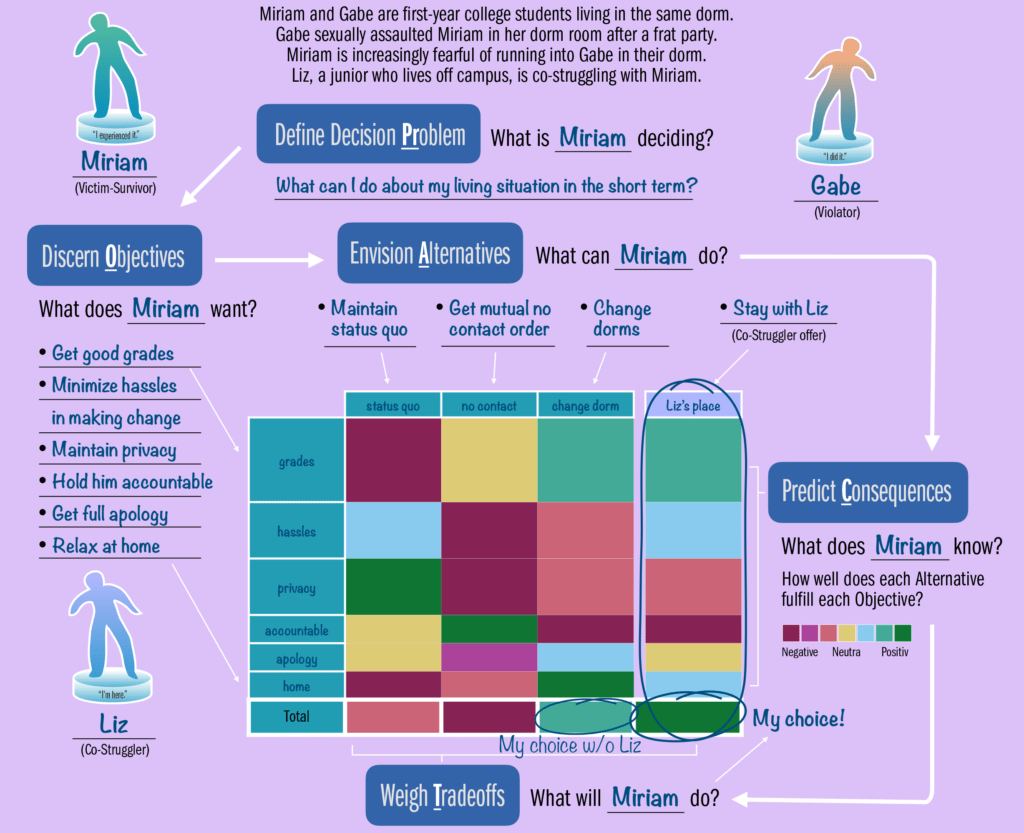

PrOACT in practice (sexual violence example)

Read about the case study here.