How to identify and manage project risks

All projects are unique undertakings that involve opportunities and risk.

The results they are expected to deliver inevitably involve unknowns and uncertainties. Uncertainty is intrinsic to projects. There will always be some level of uncertainty in a project’s outcome.

The business cases for most projects rest on the assumption that the value of the project outcome will significantly exceed the project’s cost. Sometimes there are good reasons to accept the starting assumptions regarding performance, deadlines, budgets, and other project parameters. In most cases, the initial project assumptions are based more on wishful thinking than on reliable, analytical analysis.

The very opportunities that give rise to projects contain significant uncertainty and risk. They are frequently lean and have minimal funding, staffing, and equipment. To make matters worse, there is a pervasive expectation that the next project should be completed even quicker.

Many projects are particularly risky because they are complex and highly varied. These projects have unique aspects and objectives that significantly differ from previous work or initiatives. The environment for projects is also constantly evolving or evolving quickly.

To meet aspirational goals, project managers optimise project workflow by adopting alternatives that compress plans, save money, or use other trade-offs to better conform to what their key stakeholders have requested. As such, most projects find that their initial project plans fall short of timing, cost, or other stated objectives.

Moreover, because of the aggressive objectives and expectations set at the outset of most projects, uncertainty and risk concerning the project are skewed heavily toward adverse consequences.

The number and severity of risks and issues on these projects have will continue to grow. To avoid a project doomed to failure, you must continuously innovate and consistently use the best practices available.

Unfortunately, in many organisations, there is little to no formal project management methodology mandated. Often, it is even discouraged for various reasons. Without an agreed approach to delivering projects, the achievement of project objectives and outcomes will be called into doubt.

Uncertainty and risk in projects

The impact of uncertainty on project objectives create risks for projects. Risk as defined by the international risk standard, ISO 31000, is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”.

Risk can be almost any impact or consequence of an uncertain event associated with the project. If the uncertain event is an economic downturn, then the risk or the effect of an economic downturn on the project objectives is poor project outcome.

Not all risks are equally important, though.

Three most common project risks are:

- Cost risk – Typically the escalation of project costs is due to poor cost estimating accuracy and scope creep.

- Schedule or time risk – There is a risk that project activities will take longer than expected. Slippages in schedule typically increase costs. They also delay the receipt of project benefits, with a possible loss of competitive advantage.

- Performance risk – The risk that the project will fail to produce results consistent with project specifications.

Other project risks include:

- Scope changes – Revisions made to scope during the project.

- People – Issues arising from internal staffing

- Scope defects – Failure to meet deliverable requirements.

- Schedule delay – Project slippage due to factors under the control of the project.

- Outsourcing – Issues arising from external staffing.

- Schedule estimates – Inadequate durations allocated to project activities.

- Money / financing – Insufficient project funding.

- Dependencies – Project slippage due to factors outside the project.

A key root cause of many of these project-related risks is the lack of executive and stakeholder commitment. The project team may lack the authority to achieve project objectives. In such cases, executive management support is fundamental to project success. When this doesn’t materialise, the project fails.

Therefore, at the overall project-level, there are additional risk factors that need to be managed apart from specific project risks. They include:

- Inexperience project manager.

- Weak sponsorship.

- Re-organisation and business changes.

- Regulatory and issues.

- Lack of common or better practices.

- Project assumptions.

- Poor motivation and team morale.

- Weak change management control.

- Lack of customer or stakeholder interaction.

- Poorly defined infrastructure

- Inaccurate (or no) performance metrics.

“Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it,” as the saying goes.

You can never know the precise outcome in advance for any given project. But through the review of data from earlier project work and experiences, you can improve the predictions of the potential results that you can expect.

The goal of risk management for a single project is to establish a credible plan consistent with business objectives. Thereafter is to maximise the range of opportunities or minimise the range of possible threats.

The good thing is that most of these adverse project outcomes have been experienced and well documented. All you need to do is to learn from other people’s mistakes and avoid or minimise them.

Project risk management yields many benefits

It is not possible for you to completely remove all risk and uncertainty. You can, however, manage project opportunities and risks by understanding the significant sources of risk and taking prudent actions. Your actions will either maximise opportunities for project success or minimise failure modes. Dealing with known causes of risk also minimises firefighting and chaos during projects.

Adequate risk analysis lowers both the overall cost and the frustration caused by avoidable problems. The amount of rework and unforeseen late project effort can be reduced.

Project risk management is undertaken primarily to improve the likelihood or extent of project success by achieving project objectives.

Effective project risk management either provides a credible foundation showing that a given project is possible or shows that the project is infeasible and ought to be avoided, aborted, or at least modified. Risk analysis may also uncover opportunities to improve project outcomes and increase project value.

Risk analysis uncovers opportunities or weaknesses in a project plan. It can trigger changes, new activities, and resource shifts. It may also reveal needed shifts in overall project structure or basic assumptions.

Uncertainty of project outcomes can be demonstrated.

Risk assessments build awareness of project exposures. They show when, where, and how painful the problems could be. This causes people to work in ways that avoid project difficulties or project failures.

Risk data can be useful in negotiations with project sponsors. Using information about the likelihood and consequences of potential opportunities and risks give project managers more influence in defining objectives, determining budgets, obtaining staff, setting deadlines, and negotiating project changes.

Project selection is a major source of project risks

Projects begin because of an organisation’s business decision to create something new or change something old. They are a large portion of the overall work done in organisations these days.

There is a significant ‘project risk’ even before a project is born. Choosing projects creates both opportunities risks. The processes for project selection and project risk management are tightly linked.

Selecting and maintaining an appropriate list of active projects requires proactive portfolio management of projects or program management.

This is where project selection affects project risk in several ways. Poor or ineffective portfolio or program management exacerbates a few common project risks:

- Excessively rosy expectations for project results and benefits.

- Too many projects competing for limited resources.

- Project priorities are misaligned with overall strategies.

- Inadequately funded projects.

- Unrealistic project deadlines.

- Optimistic estimates of organisational capabilities and capacities.

This is where project risk data is a critical input to any project selection process. Program management uses risk assessment as a key criterion for determining which projects to put into planning at any given time. Without high-quality risk data and credible estimates for potential projects, there could be an excessive number of projects. Many unrealistic projects could be undertaken. Many of them will fail.

Managing risk in programs

A program is a group of related projects managed in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually.

Programs, like projects, are an effective means of achieving organisational goals and objectives. They are often implemented in the context of a strategic plan. The focus is on the coordination of several related projects and other activities, over time, to deliver benefits to the organisation.

Programs are initiated to accomplish agreed outcomes that often affect the entire organisation.

Projects are best if there is one primary goal to focus on. It involves delivering a product to meet stakeholder needs and expectations. The key element in project management is efficiency.

Programs are best suited for delivering multiple goals, with a series of projects each focusing on a specific goal. They deliver combined benefits to the organisation within defined constraints and in alignment with its strategic objectives.

The key focus of program management is in maximising benefits or outcomes. It delivers value to the organisation, coordinating several related projects over time and working in concert with the operational and strategic elements of the organisation.

Effective value management is a key part of effective program management. It requires an understanding of what is valuable to the organisation. To realise a benefit, the outcomes from the program must support a strategic objective of the organisation.

In comparison, project management is focused on the efficient creation of a defined deliverable (e.g., rebuilding a school). Projects are undertaken for the efficient delivery of a defined objective or output. The processes to initiate a project within the program should be aligned with the organisation’s strategic objectives. When strategic alignment is achieved, the realised benefits are collectively translated into real value.

Managing projects and programs have distinctly different themes and focus. They each have major consequences on the style of management:

- A successful project is delivered on time, budget, and specifications, whereas a program is focused on the creation of overall benefits, taking more time, or spending more money to deliver increased benefits to achieve a good outcome. With programs, value and benefits are the key drivers rather than budget, time, and quality.

- Project managers are focused on producing optimum deliverable. Whereas, program managers are focused on integrating the deliverables into the organisation’s operations to reap the maximum benefits and outcomes from using the deliverables. The program manager must be an integral part of the organisation’s strategic business. It is virtually impossible to effectively contract out the program management role.

- Stakeholder management is far more complex. Program benefits can only be realised in the future. Project managers, on the other hand, are working within a more constrained and defined project management framework.

- The risk management framework of a project is largely definable operationally. The program risk management framework is heavily influenced strategically by external factors.

Defining the project ‘success’

Project ‘success’ can be measured in two ways:

- Project efficiency – Measured against the widespread and traditional measures of project performance of meeting timeline, budget, scope, and requirement goals. This could be referred to as ‘project management success’.

- Project success – Meeting wider business and enterprise goals as defined by key stakeholders (i.e., the sponsor, the project team, the client, and the end-users).

Many projects can finish on time and cost but are abject failures. Or many projects can finish late and overspent but are considered successful.

While project efficiency is an important contributor to project success, there will be other factors that will contribute significantly to the overall or real project ‘success’ as well. Therefore, project success is more than the achievement of project efficiency measures.

Project managers should be aware that when they plan and control the project, broader success measures must be considered and made parts of the project planning and control process. This will improve project and project manager perceived success, especially over the long term, without ignoring project efficiency goals.

Risk of insufficient project planning

This is where insufficient project planning is a risk to achieving overall project success.

Frequent change is one of the most damaging risk factors to many projects. Managing this risk requires good project planning and information.

Project planning is so vital to any project success.

You can have the most effective team. But they cannot overcome a poor project plan. Projects that start down the wrong path can only lead to the most spectacular project failures. This is where decisions made at the early definition stages set the right direction and strategic framework for project success. Plans are a cornerstone of any project. Get the project planning wrong, the project will be wrong for a long time.

In short, project management would not exist when there is no project planning.

When solid planning data is available, it can better able to resist inappropriate change, rejecting or deferring proposed changes based on the consequences demonstrated using the project plan.

If changes are necessary, it is easier to continue the work by modifying an existing plan than by starting over in a vacuum.

There could also be faulty project assumptions that persist. This could be due to inadequate or incomplete planning data. A better understanding can lead to a clearer definition of project deliverables and fewer reasons for the change.

The time required to plan is not a valid reason to avoid project management and planning processes. Although it is universally true that no project has enough time, the belief that there is no time to plan is difficult to understand.

All the work in any project must always be planned.

When projects must execute quickly, more, not less, project planning will be required. Delivering a result with value requires sequencing the work for efficiency. You must ensure that the activities undertaken are truly necessary and of high priority.

There is no time for rework, excessive defect correction, or unnecessary activity especially for fast-track projects.

Risk planning and appetite to take risk

Risk planning begins by reviewing the initial project assumptions and understanding what wider business and enterprise goals to be achieved by completing the project.

Project charters, datasheets, or other documents used to initiate a project often include information concerning risk, as well as goals, staffing and resourcing assumptions, and other information.

Projects thought to be low risk may involve assumptions leading to unrealistically low staffing and funding.

Understand the expectations and requirements of all stakeholders (i.e., project sponsor/executive, the project team, the client, and the end-users). Note any differences in your perception of project risk and the stated (or implied) risks perceived by the stakeholders.

Work to characterise the appetite for risk for your key stakeholders. Ask questions to uncover clues to their risk tolerance, such as:

- Worst case, how much overall would they be willing to invest?

- What is the minimum result that they would find acceptable?

- What are the most significant concerns they have about the project?

Integrate what you have learned about your stakeholder’s risk tolerance, preferences and requirements into your overall project planning and assumption.

If your key project stakeholders prefer to avoid risks, integrate processes for clearly defining requirements and expectations, detailed schedules with precise estimates, and quantitative analysis of opportunities, risks and uncertainties, even worst cases. Include a thorough risk analysis in your planning documents. Plan for periodic reviews to update your project plan as your project is implemented.

Even if your project is highly speculative, novel, or revolutionary, incorporate risk identification and management into all your planning processes. Provide for adequate analysis of any significant risks that you may uncover.

Tolerance for risks is not a license to take them. Your goal after all is to run a successful project that delivers good value and outcome.

As you define your project scope and create planning documents, such as a project work breakdown structure, you will uncover potential project opportunities, risks, and uncertainties.

Risk identification

Risk identification is a fundamental part of defining and analysing scope, schedules, costs, and other project plans.

As you develop planning documents, be alert to unknowns and uncertainties. Collect specific information about potential gaps, holes, and problems as you progress. List them with other opportunities, uncertainties, and risks that your project may encounter.

Review (or create) a format for your project risk and issues register. Includes the information that you will need to analyse, prioritise, and respond to risks. Risk are known opportunities and uncertainties, whereas issues are known events that must be mitigated.

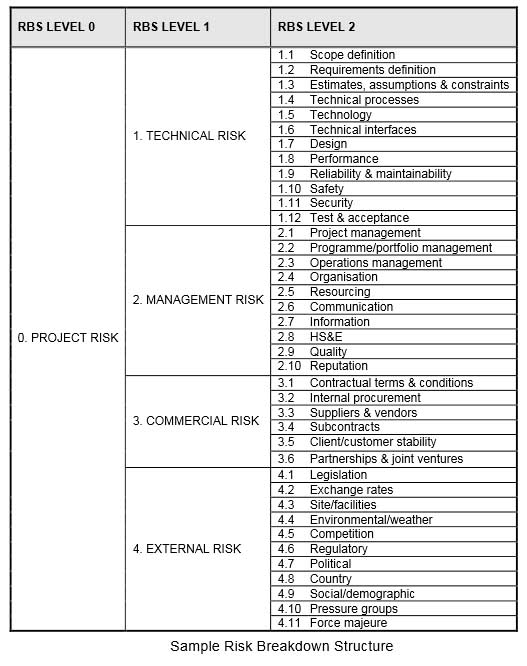

Generic risk breakdown structure for projects

Risk breakdown structure (RBS) is a hierarchical representation of all possible risks impacting a project. It starts from higher levels and going down to finer level risks. This is like the organisation of the work breakdown structure (WBS). It sets out the risk universe for projects.

An RBS for a typical project can be a useful starting point, as shown in the diagram below.

Define thresholds for project parameters that you will monitor during the project for schedule slippage, overall cost control, deliverable performance, and any other quantitative status data you plan to collect. Determine in advance what actions will be triggered whenever your project data fails to meet the defined thresholds. Set up ranges and limits.

Risk management plan

A risk management plan usually starts by summarising your risk management approach in the project, including your risk management planning information. It lists the methodologies and processes that you will use during project implementation.

Your risk management plan will state the standards and objectives for risk management on your project.

The plan defines the roles of the people who will be responsible for implementing the risk management approach. It also includes definitions and standards you plan to use with any risk management tools. The plan covers the frequency and agenda for periodic risk reviews, formats for risk management reports, and risk-related requirements for project status collection and other tracking.

For small projects, risk planning maybe informal. But for large, complex projects, develop and publish a written risk management plan for all stakeholders. Define any significant activities for risk identification, analysis, control, and review. Secure the staffing and funding to support these efforts.

Incorporate any budgets dedicated to risk analysis, contingency planning, and risk monitoring into your plans.

Another aspect of risk planning is ensuring that risk management plans include adequate attention to uncertainties that represent project opportunities.

Uncertainty in projects can swing both ways. Some activities and other work may go better than expected. Allocate at least some of your risk management efforts to consider project aspects that may result in better outcomes, along with your work in managing potential threats.

Project scope risk

A great deal of project risk can be discovered at the earliest stages of project work or planning, especially when defining the scope of the project. Early decisions to shift the scope or abandon the project are essential on projects with significant scope risks.

Managing scope risk requires a scope definition that clearly defines and state both what you expect to accomplish and what you intend to exclude. Clearly define all project deliverables. Note all challenges. Decompose all project work into small pieces. Identify work that is not well understood. Assign ownership for all project work.

From a risk management standpoint, use the is/is-not technique rather than the musts-and-wants. The “is” list is equivalent to the musts. But the “is-not” list serves to limit the scope. Determining what is not in the project specification and scope is never easy. When you fail to do it early, many scope risks will remain hidden behind a moving target.

An “is-not” list does not cover every possible thing that the project might include. It is generally a list of completely plausible, desirable features that could be included. It could be in scope for some future project — just not this one.

Sources of specific scope risks include:

- Requirements that seem likely to change.

- Mandatory use of new technology.

- Requirements to invent or discover new capabilities.

- Unfamiliar or untried development tools or methods.

- Extreme reliability or quality requirements.

- External sourcing for a key sub-component or tool.

- Incomplete or poorly defined acceptance tests or criteria.

- Technical complexity.

- Conflicting or inconsistent specifications.

- Incomplete product definition.

- Large work breakdown structure.

Mitigating scope risks involves shifts in approach and potential changes to the project objective.

Ideas for mitigating scope risks include:

- Explicitly specify project scope and all intermediate deliverables, in measurable, unambiguous terms, including what is not in the deliverable. Eliminate wants and nice to haves early.

- Gain acceptance for and use a clear and consistent specification change control process.

- Adopt iterative or agile methods to manage scope based on user and stakeholder feedback and current priorities.

- Build models, prototypes, and simulations. Get user and stakeholder feedback continuously.

- Test with users, early and often.

- Schedule risk-prone, complex work early.

- Obtain funding for any required outside services.

- Translate, competently, all project documents into relevant languages.

- Minimise external dependency risks.

- Consider the impact of external and environmental problems.

- Keep all plans and documents current.

The two broad categories of project scope risk that relate to changes and defects.

Change risk

Change happens. It is inherent in many projects.

Managing scope risk related to change relies on minimising the loose ends of requirements at project initiation and having a robust process for identifying, controlling and managing changes throughout a project.

There are three categories of scope change risks:

- Scope gaps.

- Scope creep.

- Scope dependencies.

Scope gaps are the result of committing to a project before the project requirements are complete or finalised.

When legitimate needs are uncovered later in the project, change is unavoidable. These gaps are usually due to incomplete or rushed analysis. A more thorough scope definition and project work breakdown could have revealed the missing or poorly defined portions of the project scope.

Scope creep plagues all projects, especially complex projects. New opportunities, interesting ideas, undiscovered alternatives, and a wealth of other information emerges as the project progresses. They provide a perpetual temptation to redefine the project and to make it “better.”

Scope creep can come from any direction. But one of the most insidious is from inside the project. Every day a project progresses, you learn something new. You will inevitable see things that were not apparent earlier. This can lead to well-intentioned proposals by someone on the project team to “improve” the deliverable.

Scope creep can represent an unanticipated additional investment of time, resources, and money because it requires new effort. It results in redoing work already completed. When entirely new requirements are piled on as the project is implemented, it could be most damaging.

Managing scope creep requires an initial requirements definition process that thoroughly considers potential alternatives. It includes an effective process for managing specification changes throughout a project.

Scope dependencies are due to external factors that affect the project. This is the risk that you take on whenever you have a dependency on something (or someone) else. One simple example could be that the software you are coding might depend on hardware to run on. When the server goes down, the software does not work.

Defect risk

Complex projects rely on many things to work as expected. Unfortunately, new things do not always operate as promised, as required, as planned, or as expected. Even normally reliable things may break down or fail to perform as desired.

Software problems and hardware failures are the most common types of defect risk. For example, a custom integrated circuit, a board, or a software module did not work initially and had to be fixed. Hardware may be too slow. The software may be too difficult to operate.

Integration defects, say between software and hardware, can cause project delays. For large programs, work is typically decomposed into smaller, related sub-projects that can progress in parallel.

Successful integration of the deliverables from each of the sub-projects into a single system deliverable requires not only that each of the components delivered operates as specified but also that the combination of all these parts functions as a system. When all components fail to play nicely together, your integrated system lock up, or crash.

Project scheduling risk

Scheduling risk is the likelihood of failing to meet schedule plans. It potentially exists in every schedule. It is impossible to predict.

Schedule risks may be minimised by making additional investments in planning and revising your project approach. Some ideas to consider include:

- Use expected estimates when the worst cases are significant.

- Schedule highest-priority work early.

- Manage external dependencies proactively.

- Before adopting new technology, explore possibilities for using older methods.

- Use parallel, redundant development.

- Send shipments early. Avoid reliance on just-in-time.

- Know customs requirements.

- Be conservative in estimates.

- Break projects with large staffing into parallel efforts.

- Partition long projects into a sequence of shorter ones.

- Schedule project reviews.

- Reschedule work coincident with known holidays and other time conflicts.

- Track progress with rigour and discipline, and report status frequently.

Schedule risks fall into three categories:

- Delay risks are defined as schedule slips due to factors that are at least nominally under the control of the project.

- Estimate risks are cases of inadequate duration allocated to project activities.

- Schedule dependency risks relate to project slippage due to factors outside the project.

Delay risks

Types of delay risk include parts, information, hardware, and decisions.

Parts that were required to complete the project deliverable were the most frequently reported source of delay. Parts delivery, defective parts and parts availability problems are common sources for this delay.

Information delay could be due to time differences across the globe. Regularly losing one or more days due to communication time lags or misunderstandings are common. Access to information could also inadequate.

Hardware needed to perform project work that is delivered late could be another source of delay risk.

Delays could be the result of extended debates, discussions, or indecision. Poor access to decision-makers or their lack of interest in the project could also delay projects.

Estimating risk

One of the project managers biggest difficulties is estimating. More so for complex or unique projects, especially when they can’t learn from past projects and experience. Personal judgements can be a source of project bias.

Imposed deadlines or aggressive deadlines set by stakeholders in advance, with little or no input from the project team can be a risk to the project. Even when the project plan shows the deadline to be unrealistic, these unattainable timing objectives are often retained. Such projects are doomed from the start.

Dependency risk

A dependency just suggests that one activity is reliant on another activity – i.e., activity A will start after activity B starts but in another situation activity A would start after activity B finishes. In both these situations, activity A is dependent on activity B, but the relationships are completely different.

In larger projects (often classified as programs), a few smaller projects interact and are linked by inter-dependencies. Each project within a larger program must synchronise the timing of schedule dependencies to avoid being slowed down by (or slowing down) other projects. Managing all these connections is difficult in complex programs.

Legal and regulatory dependencies can be problematic for some projects especially if there are legal and paperwork requirements related to the project to be completed.

Project resource risk

A lack of technical skills or access to appropriate staff is a large source of project risk for complex projects. Risk management on these projects requires careful assessment of the skills needed and the commitment of capable staff.

There are three categories of resource risk:

- People risks arise within the project team.

- Outsourcing risks are a consequence of using people and services outside the project team for critical project work.

- Money and funding can have a substantial impact on projects in many other ways. Budget cutbacks or restrictions can cause project delays.

People risk includes:

- Selecting the appropriately skilled project team member to perform the work.

- Loss of staff due to resignation, promotion, reassignment, health, or other reasons.

- Temporary loss of staff due to illness, hot site, support priorities, or other reasons.

- Queuing of staff due to other commitments for needed resources or expertise.

- Staff not being available at project start due to the late finish of previous projects they were in.

- Loss of team motivation, cohesion, and interest especially in long projects.

Outsourcing risk includes:

- Selecting the appropriate outsource provider.

- Late or poor output from the outsource provider. This is where your statement of work must be clear.

- Delayed starts due to contract and price negotiations, contracting, and contract management issues.

Mitigation strategies for resource risks include:

- Avoid planned overtime.

- Build teamwork and trust on the project team.

- Use expected cost estimates where worst-case activity costs are high.

- Obtain firm commitment for funding, resourcing, and staff.

- Keep customers and stakeholders involved.

- Anticipate staffing gaps.

- Minimise safety and health issues.

- Encourage team members to manage their risks.

- Delegate risky work to successful problem solvers.

- Rigorously manage the outsourcing relationship.

- Detect and address flaws in the project objective promptly.

- Rigorously track project resource use.