Science of solving problems and making decisions

Solving problems is at the core of human evolution. It is an important part life and a source of new inventions, continuous improvement, communication and learning. Applied to anticipated future events, it is used to enable action in the present to influence the likelihood of the event occurring and alter the impact if the event does occur.

Solving problems is about observing what is going on in the environment, identifying things that could be changed or improved, diagnosing why the current state is the way it is and the factors and forces that influence it, developing approaches and alternatives to influence change, making decisions under uncertainty about which alternative to select, and taking action to implement the changes.

Your everyday life and work are filled with uncertain situations for which no resolution is immediately known.

What route should I take to work to minimise traffic congestion?

How can I afford paying my children’s school fees?

How can I accelerate the collection of receivables?

What will be the most effective method for marketing the new product to new customers?

Which insurance program should I select?

These are all questions about situations that are currently unknown and therefore need to be considered, answered or solved.

Given that solving problems and decision making are complex subjects, this article seeks to provide a high-level overview of the key topics necessary for making informed decisions under uncertainty.

What are problems?

From an etymology perspective, a “problem” is:

- “A difficult question proposed for solution” – From Old French problème.

- “A question” – From Latin/Greek problema.

- “Thing put forward” – From proballein, “propose“; from pro-, “forward” + ballein, “to throw”.

In everyday language, a “problem” is:

- A question or situation that presents doubt, uncertainty, perplexity, or difficulty.

- A question proposed for solution or discussion.

The word “problem” as used in this website refers a situation with an uncertain question or issue to be considered, answered or solved. It is a ‘Question to be resolved’.

The process of consideration results in an understanding of the current and desired states of that situation.

A problem must also be worth solving or that there is a felt need. It is a ‘Question worth solving’.

Finding or solving the problem must have some social, cultural, or intellectual value to someone. If no one perceives a value or need to answer the question, then there is no problem to be considered, answered or solved.

Categorising problems

Problems can be divided into three fundamental categories as follows:

- Problems that have resulted from a change or adjustment from existing conditions, or change-related problems.

- Problems that are persistent and have seemingly been around forever and are therefore chronic problems.

- Problems that are both chronic and change-related, or what I call hybrid problems.

11 Kinds of problems

There are eleven kinds of problems to be considered, answered or solved:

- Logical problems – Logical control and manipulation of limited variables.

- Algorithms – Procedural sequence of manipulations; algorithmic process applied to similar sets of variables; calculating or producing the correct answer.

- Story problems – Disambiguate variables; select and apply an algorithm to produce correct answer using the prescribed method.

- Rule-using/rule-induction problems – Procedural process constrained by rules; select and apply rules to produce system constrained answers or products.

- Decision making – Identifying benefits and limitations; weighting options; selecting an alternative and justifying.

- Troubleshooting – Examine system; run tests; evaluate results; hypothesise and confirm fault states using strategies (replace, serial elimination, space split).

- Diagnosis-solution problems – Troubleshoot system faults; select and evaluate treatment options and monitor; apply problem schemas.

- Strategic performance – Applying tactics to meet strategy in real-time; complex performance; maintaining situational awareness.

- Policy-analysis/case analysis problems – Solution identification, alternative actions, argue a position.

- Design problems – Acting on goals to produce artefact; problem structuring and articulation.

- Dilemmas – Reconciling complex, nonpredictive, vexing decision with no solution; perspectives irreconcilable.

Three characteristics of problems

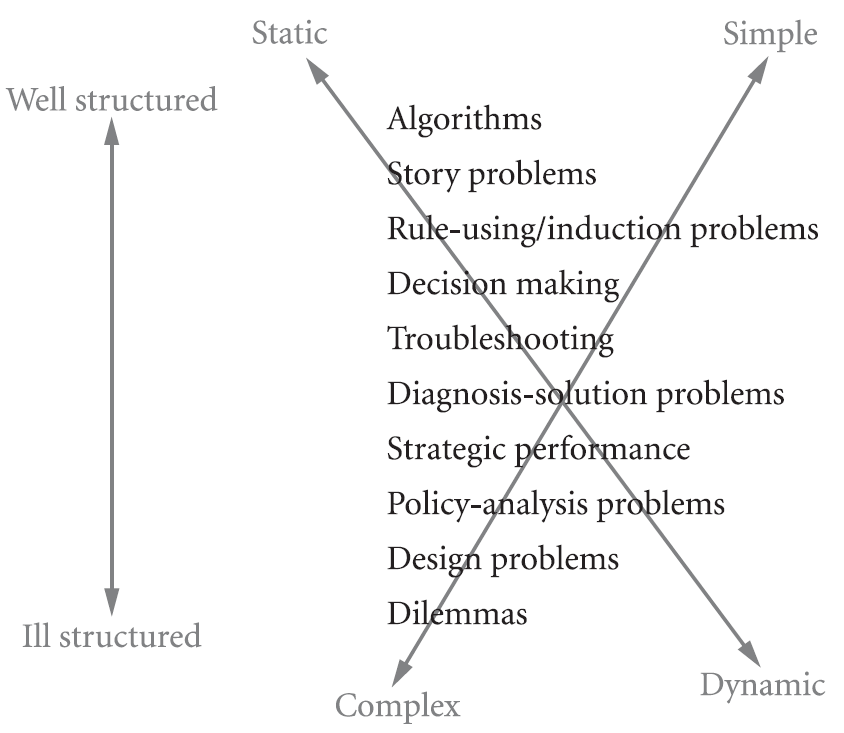

These 11 kinds of problems are influenced by three key external characteristics, as prioritised and shown in the diagram below:

- Structuredness – This is the degree to which ideas in problems are known or knowable to the problem solver.

- Well-structured problems tend to be more abstract and de-contextualised. They are not situated in any meaningful context. These problems rely more on defined rules and less on context.

- Ill-structured problems tend to be more embedded in and defined by every day or workplace situations. These problems are more subject to belief systems that are engendered by social, cultural, and organisational drivers in the context.

- Complexity – This is a function of how the problem solver interacts with the problem, determined partially by the problem solver’s experience as they interact with the problem.

- Most well-structured problems are not very complex.

- Ill-structured problems tend to be more complex.

- Dynamicity – Many problems are dynamic because their conditions or contexts change over time, converting them into different problems.

- Well-structured problems that tend to be static.

- Ill-structured problems tend to be more dynamic.

Characteristics of rational decision-making

- Ordering – A rational decision-maker is able to order the alternatives (e.g. brands and styles of washing machines) in a set of choices (e.g. all available washing machine options) from best to worst or from worst to best. In this sense, rational decision-makers will prefer some alternatives to others while leaving open the possibility of liking some washing machines equally.

- Dominance – A rational decision-maker will not select an alternative that is dominated by another alternative. So if one washing machine (Option A) is superior in terms of cost, load capacity, energy efficiency and quality to another washing machine (Option B) (assuming these were the only characteristics we were considering), then A should always be preferred to B.

- Cancellation – If two or more alternatives share a common characteristic (e.g. if three competing washing machine options share an identical cost), then this characteristic (cost) is cancelled and should be ignored when choosing among these three machines. Thus, a choice among alternatives should depend only on those characteristics that differ and not on shared characteristics.

- Transitivity – If a rational decision-maker prefers washing machine A to washing machine B, and washing machine B to C, then s/he should also prefer washing machine A to C. In other words, a preference order of A > B > C also implies A > C, which is known as transitivity in choice.

- Invariance – A rational decision-maker will not be influenced by seemingly alternative, but essentially identical, “frames” of the same set of choices. Imagine (1) claims that a washing machine will provide savings of $100 (out of a potential maximum of $135) per year on utility bills and (2) claims that a washing machine will provide savings of $35 less than the potential maximum of $135 per year on utility bills. Rational decision-makers should be indifferent between two essentially identical but seemingly alternative frames of the plan. This situation is referred to as the principle of invariance.

- Continuity – A rational decision-maker will base choices on the expected value of the available alternatives, which will lead to choosing the alternative with the largest expected payoff. Imagine a choice between (1) an inexpensive, but inefficient, washing machine (whose operating costs will be high) and (2) an expensive and efficient washing machine that will provide savings over the life of the washing machine, recouping the initial purchase cost and then some. Rational decision-makers should prefer the more expensive washing machine option.

Decision making problem

A decision is a choice between two or more alternatives that involves an irrevocable allocation of resources.

Decisions are about the future, which is inherently uncertain. You must deal properly with uncertainty to make good decisions.

Decisions come in all types and sizes, but all of them have one thing in common: The best choice creates the most potential for what you truly want.

To find that best choice, you need to reach decision quality. You must recognise decision quality as the destination. Clearly, you cannot reach your destination if you are unable to visualise or describe it. Nor can you say, “I have arrived!”, with any confidence.

Decision making is one of the most common form of problem-solving types in our everyday lives. Countless decision-making problems are considered, answered or solved without conscious awareness.

Should I say “Hi” to that person or pretend I did not see him?

What should I wear to work today?

Should I move in order to take another job?

Should I select this person for employment?

What is the best material for manufacturing industrial parts?

What is the best treatment option for this medical patient?

A decision is a choice made from various available alternatives.

Decision making refers to a process by which you select a course of action among several alternatives to produce a desired result, which may or may not result in an action. There is a set of alternative criteria that decision makers work through to identify the optimal solution.

Doing nothing and keeping the status quo is also a decided solution.

Part of problem-solving is critical thinking. This is where you objectively analyse and evaluate an issue in order to form a judgement, where possible or appropriate.

Critical thinking is purposeful, reasoned, and normally goal directed. It is thinking that is directed toward solving problems, deducing inferences, calculating probabilities, and making decisions. It is what psychologists call a higher-order skill.

Given that decisions are made every day — at work and in our personal lives — it’s surprising that smart decision making is not taught in school. It’s the kind of skill everyone should have in their mental toolkit.

Types of decisions made

The different types of decisions that can be made are set out in the table below.

| Individual decisions Decisions taken by a single individual during regular routine work according to the policies of the organisation, team, group or committee. | Group decisions Decisions taken by an organisation, a team, a group or a committee formed for a specific purpose to make an informed decision. |

| Informal decisions Informal decisions that a person makes as an individual, which has a direct impact on the individual. | Formal decisions Formal decisions that a person makes as a member of an organisation, a team, a group or a committee using formal authority. |

| Rational/fact-based decisions Decisions made after careful and systematic analysis of a problem and evaluation of several alternatives based on rational and logical facts, figures and evidence. | Irrational/intuition-based decisions Decisions based on your intuition or experience and not based on relevant facts, figures and evidence. |

| Programmed decisions Routine and repetitive decisions using pre-established rules and procedures. | Un-programmed decisions Decisions concerned with unique problems for which no preestablished rules and procedures have been made. |

| Strategic decisions Strategic decisions have long-term or material impact on the organisation. For example, launch of a new product or services and buying another business. | Operational decisions Operational decisions are the day-to-day decisions that have only a short-term impact on an organisation. For example, scheduling employees. |

Not all decisions are created equal. Different types of decisions require different approaches.

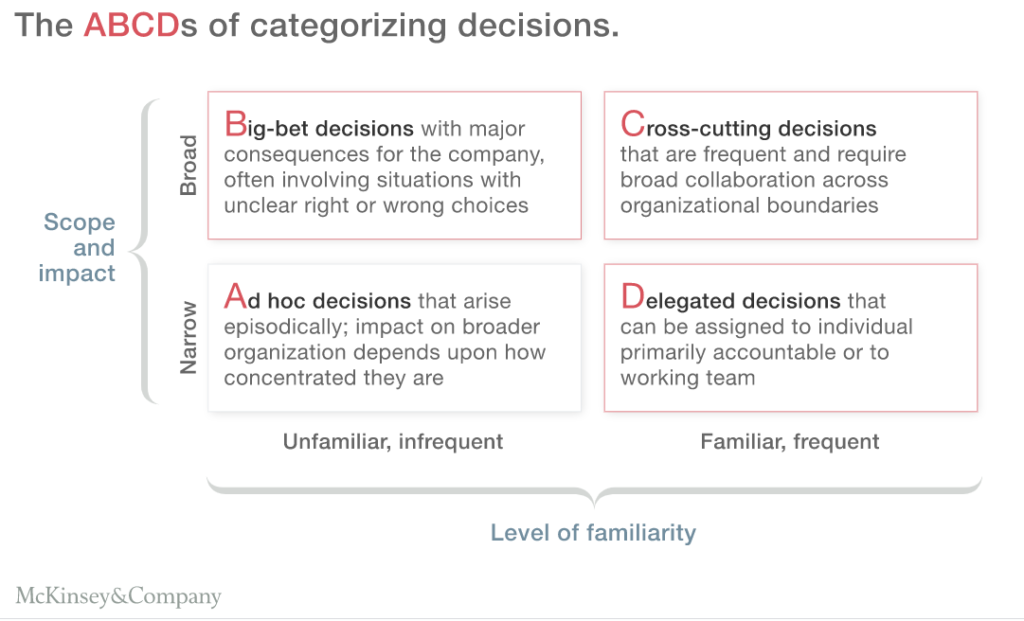

ABCD decisions

McKinsey identified four decision types – big-bet, cross-cutting, ad-hoc and delegated decisions.

Reversible and irreversible decisions

In his 1997 letter to Amazon’s shareholders, Jeff Bezos said that one common pitfall that hurts organisations, and their speed and inventiveness is a “one-size-fits-all” decision making.

Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible at the point of deciding. They are one-way doors.

These decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and don’t like what you see on the other side, you can’t get back to where you were before.

These are called Type 1 irreversible and highly consequential decisions. They are few in numbers.

But most decisions aren’t irreversible. Instead, they are changeable and reversible. They’re two-way doors.

You don’t have to live with the consequences for long. You can reopen the door and go back through again.

These are called Type 2 reversible decisions.

Carefully distinguish these two kinds of decision – Type 1 or Type 2 – when you think about taking risk and making informed decisions amid uncertainty.

If a decision is reversible, you can make it fast and without perfect information. Take risk and stop viewing mistakes or small failures as disastrous. View them as information that informs future decisions or improvements.

If a decision is irreversible, you had better slow down the decision-making process. Ensure that you take time to consider the information and understand the problem as thoroughly as you can.

These decisions can and should be made quickly. Empower people to make decisions and learn from their mistakes. Create a learning culture instead.

The reality is that most irreversible decisions can be reversible over time. But it will take effort and commitment to unwind the consequences of so-called irreversible decisions.

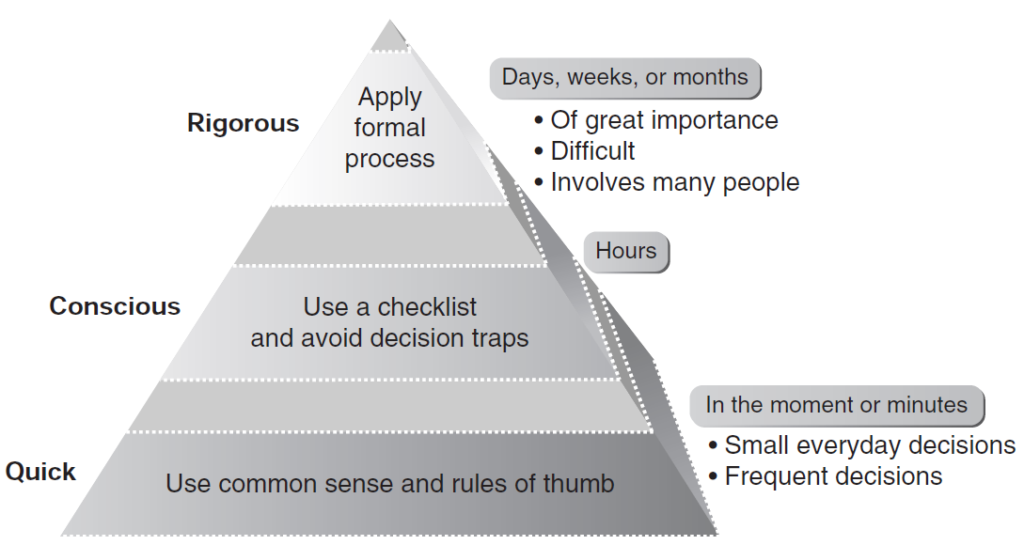

Hierarchy of decisions

You can deal with simple decisions in a few minutes using common sense or some rules of thumb. You do not need an extensive analysis to decide what to have for breakfast.

More complicated decisions, however, are worthy of more thought. Using a simple checklist to remind you of things to consider and to help you identify common decision-making errors might make the process easier. Examples of more complicated decisions are where to spend a vacation, or whether to buy a new television set.

The most important decisions you face deserve a much more refined analysis. They may involve elements of complexity, dynamics, and far-reaching consequences. They are worthy of, but frequently do not receive, the structured, rigorous decision process.

Different aspects of decision making

There are different aspects of decision-making, which have been used inter-changeability:

- Decision making styles refers to personality, thought processes, and behavioural elements that are part of the decision-making process, individually or in groups. Examples include collaborative, emotional, and rational decision-making styles.

- A decision-making process will provide a defined set of steps, that when followed, guide you to a decision outcome. The process used will be contextual. There is NO one-size-fits-all process to cater for all situations.

- Decision making techniques describe specific analysis tactics and schemes that can be used in context in the decision-making process.

- A decision-making model is a representation of the information contained in a decision and the relationships that exist between related decisions.

Decision-making styles

Your decision-making style will influence the decisions made and their outcome.

Using the wrong decision-making style may lead to a disaster. Imagine a commander using a consensus decision style while in the middle of a battle where every second could cost lives. Alternatively, using an autocratic style for a highly complex strategic decision could cut off the decision maker from the valuable input of experts.

While external factors and contextual situation are hard to predict and control, understanding your own decision-making style to making better decisions.

Nobody has a fixed set of cognitive styles. These shifts are based on the current situation, the decision to make, and many other factors.

There are three common decision-making styles:

- Intuitive vs. rational – Human beings operate by two minds, an intuitive mind, which learns directly from experience, is pre-conscious, operates automatically, and is intimately associated with emotions. Or the rational mind, which operates according to logical inference, is conscious, deliberative, and relatively emotion-free.

- Intuitive decision-making is more instinctive, subjective, less structured and subconscious in nature. It takes into consideration the following:

- Pattern recognition – Seeing patterns in events and information, and using them to figure out a course of action.

- Similarity recognition – Seeing similarities in previous situations and recognising the cause and effect of a given situation.

- Salience – Understanding the importance of information and the way it can affect personal judgment.

- Rational decision-making is a structured and sequential approach to decision-making, aimed at seeking precise solutions to well-defined problems using precise methods. The decision-maker derives the necessary information by observation, statistical analysis, or modelling. It makes a systematic analysis of such ‘hard’ quantitative data to choose from the various alternative courses of actions.

- Intuitive decision-making is more instinctive, subjective, less structured and subconscious in nature. It takes into consideration the following:

- Maximising vs. satisficing – People tend to fall under one of two main cognitive styles. Maximisers try to make an optimal decision, whereas Satisficers simply try to find a solution that is good enough.

- Maximising decision-making involves expending time and effort to ensure you have solved something as best as possible. It requires exploration and analysis to ensure “the best” option has not been overlooked and that you have confidence in your evaluation of all options. Maximisers then make better choices. Relying heavily on external sources for evaluation, they usually take longer to decide, thinking carefully about the potential outcomes and corresponding trade-offs. Rather than asking yourself if you enjoy your choice, you are more likely to evaluate your choice based on reputation, social status, and other external cues. You will also tend to regret your maximised decisions more often.

- Satisficing decision-making involves picking the first option that satisfies the requirements. You prefer a faster decision to the best decision. It means not getting paralysed by the pursuit of “perfect”. But it often does not result in the very best solution. Satisficers enjoy their choices more, spend less time and create less stress in making the choice. You ask whether your choice is excellent and meets your needs, not whether it is really “the best.”

- Combinatorial vs. positional – The combinatorial style is characterised by a very narrow and clearly defined material goal. People tend to use this style when the objective is clearly defined. The decision-making process is more about how you will achieve your goal rather than deciding on which goal to achieve. In contrast, you use the positional style when the goal is not as clearly defined. You make decisions to absorb potential risks, protect yourself, and create an environment where it’s less likely to experience the negative effects of unexpected outcomes. Aron Katsenelinboigen proposed this description based on how the game of chess is played.

- Combinatorial decision-making involves a chess player who has an outcome in mind, making a series of moves that try to link the initial position with the outcome in a firm, narrow, and more certain way. The name comes from the rapid increase in the number of moves you must consider for each step as you look ahead.

- Positional decision-making involves a chess player setting up strong positions on the board and preparing to react to the opponent. You use this strategy to increase your flexibility, creating options as opposed to forcing a single sequence.

Decision-making process

Decision making is a problem-solving process that aims to eliminate barriers or increasing the success to achieving individual or organisational goals. Have a goal in mind for effective decision-making.

The purpose is often forgotten in the decision-making process, unfortunately. A narrowly focused purpose may overlook other opportunities or possibilities. This may lead to fewer alternatives or solutions.

By defining the problem and the purpose as broadly as possible, you are able to find more significant and far-reaching results.

The decision-making process used will be contextual. There is NO one-size-fits-all process to cater for all situations.

There is, however, no universal best process or set of steps to follow in making good decisions. The process has to be tailored to the situation—more specifically, to its magnitude (or importance) and complexity, and to its inherent difficulties.

Problems are grounded in sets of assumptions about the world. Identifying and understand those assumptions you make is important. Whether you see an event or situation as a ‘problem’ depends on your view of the world.

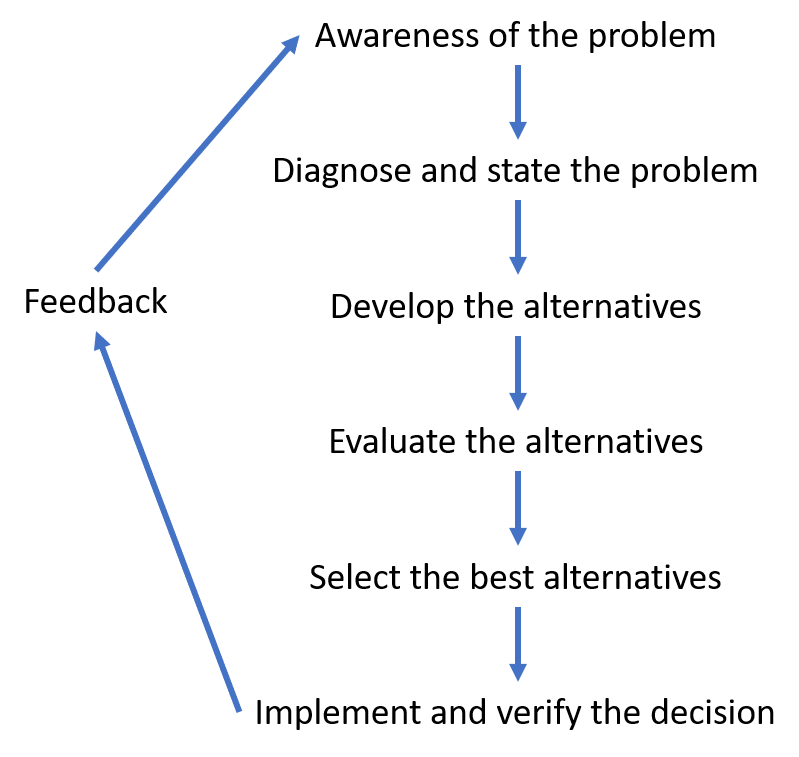

There are many processes for making decisions. They follow very similar steps or have similar activities, as shown in the diagram below:

- Awareness of the problem – At this stage, be aware about a problem to be considered, answered or solved.

- Diagnose and state the problem – Understand and analyse the problem. There are attempts to describe the problem. Objectives to be achieved through solution are known.

- Develop the alternatives – Collect data or evidence regarding the problem. Formulate different alternate course of action to solve the problem.

- Evaluate the alternative – This step involves evaluation of the various alternatives based on the feasibility of a particular action, context or situation, resources available, and time period to achieve the objectives.

- Select the best alternative – After analysing and evaluating the possible outcomes of each course of action, select the most suitable and feasible option.

- Implement and verify the decision – The next step involves implementing the decision and making sure that the selected course of action meets the expected outcomes. Follow up strategies are prepared to react towards any counter moves of others affected by the decision.

- Feedback – This is a continuous process where feedback from all the parties involved with implementing the decision is taken. Feedback may reveal another problem created due to implementation or hindering effective implementation, which calls a new decision and so on.

The problem-solving process for solving well-structured and ill-structured problems will likely differ, as shown in the table below.

| Problem solving process for well-structured problems | Problem solving process for solving ill-structured problems |

| Step 1 – Problem representation Step 2 – Search for solutions Step 3 – Implement solutions | Step 1 – Learners articulate problem space and contextual constraints Step 2 – Identify and clarify alternative opinions, positions, and perspectives of stakeholders Step 3 – Generate possible problem solutions Step 4 – Assess the viability of alternative solutions by constructing arguments and articulating personal beliefs Step 5 – Monitor the problem space and solution options Step 6 – Implement and monitor the solution Step 7 – Adapt the solution |

You can determine the type of decision-making process to use by asking the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the decision?

- Why is it important?

- Who should be involved?

- What makes the decision hard?

Decision-making techniques

Decision making techniques fall into three major categories – random; intuition based; or analytical. Different decision-making techniques can provide unique advantages for specific decisions.

Here are some common decision-making methods you can use to improve your decision-making outcome.

- A simple decision tree helps visualise multistage decision problems while addressing uncertain outcomes. It can be useful in deciding between strategies or investment opportunities with constrained resources.

- Pros-and-cons is an age-old approach of looking at the advantages and disadvantages of two options at a time. You can also consider the favourable and unfavourable factors or reasons.

- Multi-voting is used for group decisions to choose fairly between many options. It is best used to eliminate lower priority alternatives before using a more rigorous technique to finalise a decision on a smaller number of options.

- Cost-benefit analysis is generally limited to financial decisions. It can provide data for the evaluation of financial criteria in other decision-making techniques.

- Net Present Value (NPV) and Present Value (PV) calculations are often used for capital budgeting and investment decisions. NPV is sometimes considered a single criteria decision technique.

- Trial and error approach to learning has provided the basis for decision making from our childhood. The consequences for decision failure should be small. Proper reflection must be done after the trial and error to ensure that correct cause/effect relationships are identified in the learning.

- The scientific method is used to further confirm or refine a hypothesis.

- Pareto analysis, which is based on the Pareto Principle, helps in identifying changes that will be the most effective. The principle is named after economist Vilfredo Pareto, who found that an 80/20 distribution occurs regularly in the world. In other words, 20% of factors frequently contribute to 80% of the organisation’s growth.

- SWOT analysis breaks down the situation into four distinct quadrants:

- Strengths – What can you do better than your competitors? Think of both internal and external strengths that you possess.

- Weaknesses – Where can you improve? Take a neutral approach and consider negative factors.

- Opportunities – Look at your strengths. Think of how you can leverage them to create new openings for yourself. Consider how eliminating a specific weakness could open you up to new opportunities.

- Threats – Determine what challenges stand in the way of achieving your goals. Identify the primary threats.

The international standard, ISO 31010 Risk assessment sets out 39 different possible assessment techniques that you could consider using to help you weigh up the different alternatives and find the appropriate solution to your problem.

A decision-making model is a representation of the information contained in a decision and the relationships that exist between related decisions.

Decision-making model

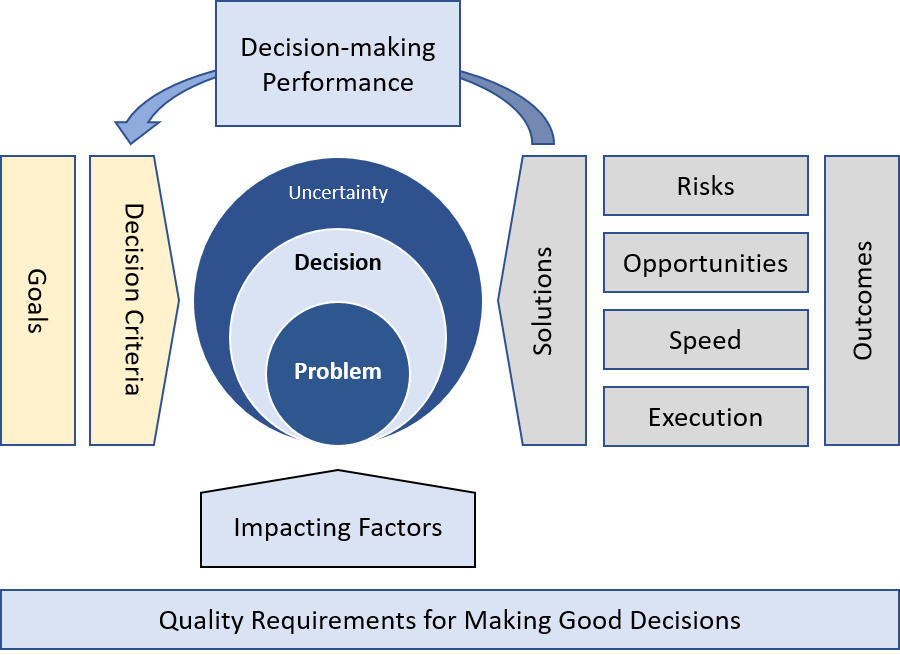

A simplified decision-making model, as shown in the figure below, consist of the following components:

- Starting with a problem to be considered, answered or solved, making a decision under uncertainty is at the centre of the decision-making model. There will be several internal and external impacting factors on the decision that you are going to make.

- To arrive at a decision, you need a decision criteria that is aligned to your goals and values. Your decision criteria is based on several other related decisions. It answers the question, “What do I value in this decision?”

- To decide, you need alternatives or solutions that have been identified and assessed. Linked to each solution are risks, opportunities and actions that must support the outcomes you want to achieve. This is where your chosen solution must be implemented effectively and efficiently.

- The speed at which you decide, respond and implement the chosen solutions will be determined by the speed at which your context or circumstance changes.

- A decision isn’t truly made until resources have been irrevocably allocated to its execution. You need a commitment to action and a mental shift from thinking to doing.

- The degree that your implemented solution meets your decision criteria is your decision-making performance.

- In the face of uncertainty, you can only judge the quality of a decision at the time it is being made, not after the outcome becomes known. Because you can control the decision but not the long-term outcome in the face of uncertainty, there are six quality requirements for making good decisions: (1) an appropriate frame, (2) creative alternatives, (3) relevant and reliable information, (4) clear values (preferences) and trade-offs, (5) sound reasoning, and (6) commitment to action.

A model that supports your decision-making process

A decision is a choice made from various available alternatives. When there are no choices that need to be selected from, there is no decision to be made.

You decide because there is problem to be consider, answered or solved. There is also an opportunity that is at hand.

Always start by defining the problem to be solved, rather than jumping into solutions. Your decision statement should be in the form of cause-and-effect. For example, “high levels of toxicity in waterways threaten the presence of rare flora in the park.”

Do ask the following questions:

- What is your decision environment?

- What needs must be addressed?

- Who is impacted?

- What information is available (watch out for information overload)?

- What is the value of the decision?

- When is the decision needed, considering the speed of uncertainty?

Decision-making under conditions of uncertainty

As a decision maker, it would be ideal if you have all the required knowledge to make decisions. This is where you are making decisions under conditions of uncertainty.

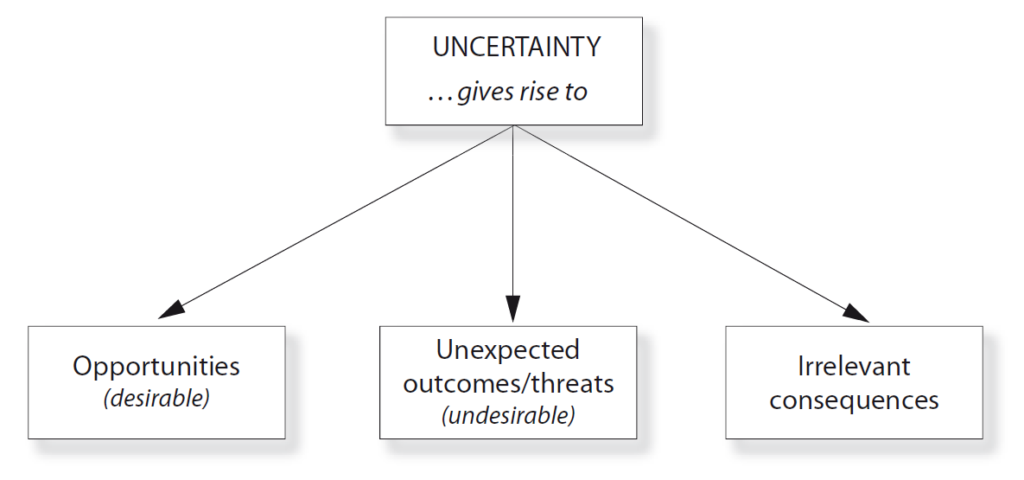

Uncertainty encompasses both opportunity and threat, as shown in the diagram below. The plans that you formulate need to take account of both.

The missing knowledge that characterise uncertainty can be categorised into four:

- Uncertain information – This includes missing information, unreliable information, conflicting information, noisy information, and confusing information.

- Uncertain understanding.

- Uncertain tempo.

- Uncertain complexity.

The reality is that you will not have all the information to make decisions.

In most cases, you will have to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty, rather than under conditions of certainty, where you have all the information. This means that you will have less control over the outcomes are you are trying to achieve.

Uncertainty, according to the international risk standard ISO 31000, is the deficiency of information that is related to the understanding or knowledge of an event, its consequence, or its likelihood.

Deciding under uncertainty is at the centre of the decision-making model.

Information quality

The characteristics of good quality information for making informed decisions are interrelated. They can generally be defined using an acronym ACCURATE:

- Accurate – Information should be fair and free from bias and errors.

- Complete – Information should be telling the whole truth, complete with facts, figures and evidence.

- Cost-beneficial – Information should be analysed for its benefits against the cost and effort of obtaining it.

- User-targeted – Information should be communicated in the style, format, detail and complexity which address the needs and requirements of users of the information.

- Relevant – Information should be communicated to the right person who has some control over decisions expected to come out from acquiring the information.

- Authoritative – Information should come from reliable or authoritative sources.

- Timely – Information should be communicated in time so that the receiver of the information has enough time to decide appropriate actions based on the information received. What is timely information will depend on situation to situation. In this era of high technological advances, out-of-date information can keep an organisation from achieving their goals or from surviving in a competitive arena.

- Easy to Use – Information should be understandable to the users or decision-makers.

Issues that relate to the quality of information includes:

- Data is not available.

- Obtaining data may be expensive.

- Data may not be accurate or precise enough.

- Data estimation is often subjective.

- Data may be insecure.

- Important data that influence the results may be qualitative.

When faced with uncertainty, rather than looking primarily to other people, authority figures, or peers for direction, look to empirical evidence. Rely upon direct observation, experimentation, and direct engagement with tangible evidence. Make bold, creative moves from a sound empirical base, where possible or appropriate.

Maintain a very calm stance in the face of uncertainty, including a willingness to let time pass when the risk profile remains stable.

How to approach complex situations

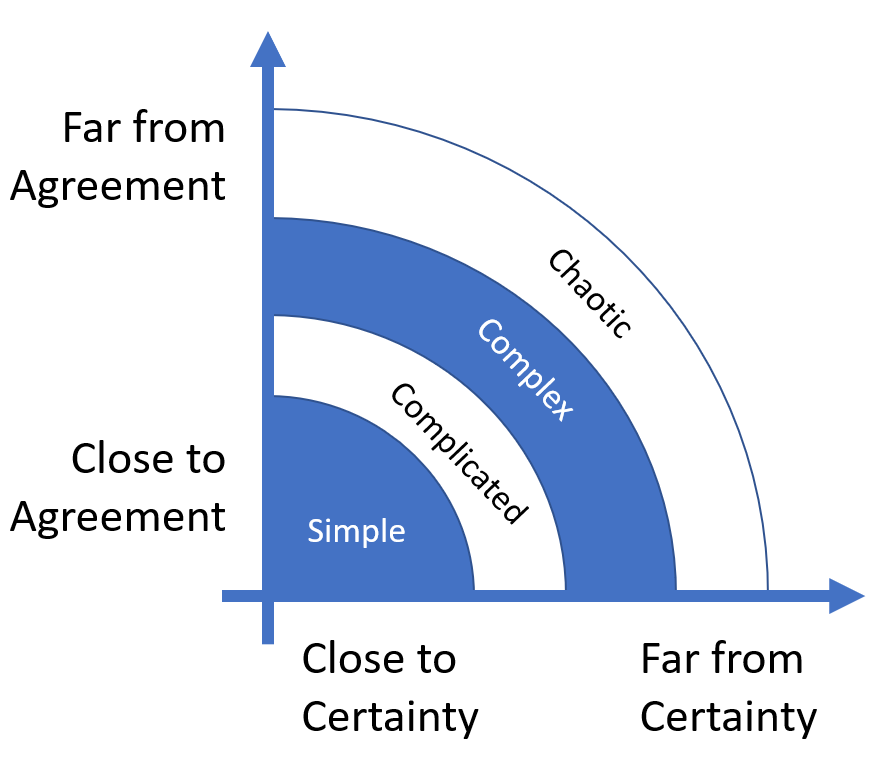

The Stacey Matrix, shown below, is designed to help understand the factors that contribute to complexity and choose the best management actions to address different degrees of complexity. The matrix is two dimensions – agreement and certainty.

| Close to Certainty | Issues or decisions are close to certainty when cause and effect linkages can be determined. This is usually the case when a very similar issue or decision has been made in the past. One can then extrapolate from experience to predict the outcome of an action with a good degree of certainty. |

| Far from Certainty | At the other end of the certainty continuum are decisions that are far from certainty. These situations are often unique or at least new to the decision makers. The cause and effect linkages are not clear. Extrapolating from experience is not a good method to predict outcomes in the far from certainty range. |

| Agreement | The vertical axis measures the level of agreement about an issue or decision within the group, team or organisation. As you would expect, the management or leadership function varies depending on the level of agreement surrounding an issue, especially the agreement on what to achieve. |

A slightly modified version of the matrix can be utilised to categorise problems and decision-making approaches in one of four domains.

The degree of certainty (the horizontal axis) relates to the quality of information available for making informed decisions. Good quality information leads to rational, analytical planning.

The degree of agreement (the vertical X-axis) relates to how much people agree with the outcomes to be achieved as a result of applying the best information available.

The matrix has now four domains.

- Simple Domain – When you exactly know what to achieve and you have good quality information to decide, the problem appears in the simple domain. There are well-established knowns and a clear relationship between cause and effect. Best practices work in this domain, which suits the command and control leadership style.

- Complicated Domain – When there is some doubt as to what to achieve and the quality of information is not so good, there will be a few unknowns. You need to analyse the situation. The good thing is that there is more predictability than unpredictability. In this domain, supervisory leadership works best with good practices.

- Complex Domain – When there is disagreement as to what to achieve and the quality of information is average to poor, there will be more unknowns than knowns. There is more unpredictability than predictability. Leaders need to probe, sense and act. They need to create boundaries within which people can call to action. Good or best practices may not work in this domain since there are a lot of unknowns. What helps in this domain are emergent practices. The leadership which suits this domain is the “servant-leadership”, where the leader serves his/her people.

- Chaotic Domain – This domain is characterised by a lot of uncertainty, unpredictability and disagreement. There is no clarity on the outcomes, state and information. There is no direct relationship between cause and effect. None of the good, best or emergent practices will work in this domain. You must act first, sense and then respond. It needs to bring some order to the chaos first and then look for solutions. This domain tends to suit entrepreneurs.

Therefore, to be successful, you need to consider the limitations and uncertainties associated with what you must achieve and the quality of information that is available to decide.

Different ways you can respond to uncertainties

Your response to uncertainties or challenges is to either cope with the uncertainty or reduce the uncertainty.

- Uncertainty coping impacts your exposure across a wide range of uncertainties. In some cases, this requires you to change your actions or strategies.

- Uncertainty reduction, on the other hand, minimises your exposure to uncertainties without changing your actions or strategies. This is a natural, primary motivator and fundamental need that guides your behaviour and actions.

There are three ways you can reduce uncertainty:

- Information gathering can be used to avoid risky decisions. You act when the gathered information is considered enough to become successful. It is primarily used to minimise demand, competition and cultural uncertainties.

- Proactive collaboration or cooperation is the second way to increase the predictability of your success. Information sharing is an essential part of collaboration and cooperation.

- Uncertainties can also be reduced through networking. This involves collecting data through social relationships.

There are five approaches for coping with uncertainty:

- Flexibility is exhibited through diversification and adaptation. Diversification helps organisations cope with industry uncertainties through its involvement in different markets or diversification of its products and services. Operational adaptation is sought through the adaptation of organisational structure or strategy.

- Imitation involves mimicking a rival’s strategy or actions.

- Reactive collaboration or cooperation approach seeks to cope with environmental and industry uncertainties.

- You may also choose to control the uncertainty rather than to passively accept it.

- Vertical integration with suppliers is used as an attempt to control input and demand uncertainties.

- Horizontal integration like mergers and acquisitions is used to control uncertainties related to competition.

- Uncertainty avoidance takes place when the level of uncertainties is unacceptable. You can postpone your actions or the implementation of your strategy as a means of avoiding uncertainty.

Therefore, there are several ways you can cope with or reduce the uncertainties that may impact the achievement of your objectives.

Factors impacting your decisions

There are many factors that can impact your decisions. These factors can be grouped into six:

- Social factors

- Cultural or unseen iceberg constraints and sub-cultures – Culture can positively or negatively impact decisions and the decision-making processes. Like the unseen parts of an iceberg, there are many unseen cultural and moral influences that you are not aware of but must navigate around to decide on the preferred choice.

- Social class – Lower-class individuals were mainly oriented toward their personal needs.

- Family, friends, peer groups, colleagues, etc. – You can be influenced by people around you.

- Situational factors

- Location – Faced with the same problem, you may make different decisions just because you are in a different location.

- Time – Decision situation can change very rapidly over time. What appeared to be a rational decision at one time might later appear to be anything but that.

- Number of choices – Analysis paralysis occurs when you overthink a decision and can’t make a choice. It could happen when there’s too much information or too many choices. Eliminating choices can greatly reduce the stress, anxiety, and busyness of our lives.

- Decision support – Many theories, tools and techniques have been developed to support and explain decision making. For example, in medical, legal and organisational contexts.

- Hunger – How hungry you are can significantly alter your decision making, making you impatient. You are more likely to settle for a small reward that arrives sooner than a larger one promised later.

- Decision fatigue – People can have a limited amount of mental energy to devote to making choices, especially at the end of the day.

- Escalation of commitment and sunk outcomes – You tend to continue to make risky decisions when there is responsibility for the sunk costs, time, money, and effort already spent on a project.

- Psychological factors

- Motivation – Decisions begin with needs. Having needs can be a motivating factor to decide and act.

- Learning – You can change your beliefs, faiths, likes and dislikes through learning and experimentation.

- Lifestyle – Eat healthy food, getting enough sleep, exercising, and exposing yourself to nature can improve your decision-making. For example, lack of sleep can have a negative impact on good decision making.

- Attitude and beliefs – People will likely vote when they believe their vote counts.

- Skin in the game – When you believe what you decide matters, you are more likely to decide.

- Fear – You can fear making decisions either because you do not want to take ownership for the consequences, or you were discouraged in the past.

- Framing – The way in which a choice is presented makes such a huge difference in how likely you select option A or option B.

- Organisational or community factors

- Contextual variables – Size, technology, environmental uncertainty, demographics, interdependence, etc.

- Structural variables – Differentiation, centralisation, division of labour, managerial, etc.

- Individual/personal factors

- Demographics – Age, gender, stages in the life cycle, education, occupation, economic position, etc.

- Stress – Chronic stress skews decisions toward higher-risk options.

- Cognitive – Biases, assumptions, self-imposed constraints, risk of failure, memory constraints, world-view constraints, language constraints, etc.

- Knowledge of the subject – Previous knowledge of a subject can cloud your decision making when presented with new information.

- Emotions – Different emotions affect decisions in different ways. If you are feeling sad, you might be more willing to settle for things that are not in your favour.

- Courage – It takes a lot of courage and confidence to act on decisions.

- Decision-making style – The way a decision-maker thinks and reacts to problems could be autocratic, democratic, or consultative.

- Characteristics of the decision-maker – This include age, personality, vision, mission, core beliefs, cognitive style, previous decision-making experience, expectations, interest, tolerance for ambiguity, individualistic/collectivistic orientation, hierarchical position in the organisation and decision-making orientation.

- Factors that relate to the decision-making process itself

- Acquisition biases – Availability, selective perception, frequency, base rate, illusory correlation, data presentation, framing, etc.

- Processing biases – Inconsistency, conservatism, non-linear extrapolation, etc.

- Information sources – Source consistency, data presentation, etc.

- Decision environment – Time pressure, information overload, distractions, emotional stress, social pressures, etc.

- Processing heuristics – Habits/rules of thumb, anchoring and adjustment, representativeness, justifiability, the law of small numbers, regression bias, best guess strategy, etc.

- Output bias – Question format, scale effects, wishful thinking, the illusion of control, etc.

- Feedback bias – Misperception, failure/success attributions, logical fallacies in a recall, hindsight, etc.

Decision-making criteria

To arrive at a decision, develop the criteria for making the decision. Your decision-making criteria will be based on several other related decisions that can be influenced by your vision, mission, core belief, personality, appetite for risk-taking, etc.

All these together with your decision criteria must be aligned to your goals that you want to achieve.

The decision criteria are those variables or characteristics that are important to the individual or organisation when assessing and making the decision. The criteria should help evaluate the alternatives from which you are choosing.

A good decision is determined by identifying the most relevant factors and ranking them in terms of importance.

Disregard any characteristics that are constant among the alternatives. For example, if all cars that you are evaluating get the same mileage, then disregard that characteristic as it will not help you choose between alternatives.

Your decision criteria should be measurable. It should be within scope of the problem you are trying to solve.

Alternatively, you should at least be able to compare one to another. For example, the typical software characteristic “user friendly” is not measurable. You could either list out what makes the application user friendly for you, or you can try out the applications and have a ranking on relative “user friendliness” between them.

These are some typical criteria for deciding:

- Comfort.

- Convenience.

- Cost.

- Effectiveness.

- Efficiency.

- Efficiency.

- Features.

- Functions.

- Opportunity cost.

- Performance.

- Quality.

- Reliability.

- Resilience.

- Return on investment.

- Style.

- Sustainability.

- Time.

- Usability.

Brainstorm the decision criteria when it involves a group decision-making. This helps ensure buy in of the decision itself because the criteria are measurable. It is not just a “well I feel like we should buy this product because I like it.”

You might also weigh the decision criteria. For example, cost savings might have a higher weight than ease of use.

Your intended goals will guide the decisions you make

Every action you take must bring you closer to the goals or successes you want to achieve. The prioritisation of your actions and limited resources will be vital to the achievement of your success.

Goals that you want to achieve must be translated into an objective decision criteria that will be used to evaluate all possible solutions (alternatives) and make informed decisions on the best choice or preferred solution.

Knowing what success looks like for you and how you can measure that success will enable you to better define and clearly articulate your decision criteria. Understanding your destination will effectively guide your decisions.

Identifying alternate solutions

Identify or create decision alternatives. Consider as many alternatives or potential solutions to your problem or opportunity. Some of these may be outside your comfort zone.

Potential solutions should be adequately described to make them understandable to everyone involved in the decision-making process. Consider new opportunities. Look at a broad range of alternatives.

There are three categories to consider when looking for known decision alternatives:

- Solutions for the same decision made previously – Solutions that have worked in the past may be a good answer for the current decision. Particularly if there is no new need or desire motivating change.

- Decision options not pursued for the same decision made previously – Decision alternatives that were considered previously often continue to evolve and improve. Previously discarded options may provide the solution needed or desired now.

- Solution alternatives for the same decision made for a different situation or context – This category requires considering different situations or environments where a similar decision might be made. For example, finding a parallel decision made in a different industry could provide some innovative solutions for meeting your success criteria.

Brainstorming well-suited to generating many alternative solutions to problems.

Assess your alternate solutions and identify the preferred response

Evaluate the alternatives based on the decision criteria once you have a list of alternate solutions. You may want to test or experiment with your solutions for feasibility.

Select the right decision-making technique to assess the alternate solutions against your decision criteria. When there is an exact or best match against your decision criteria that will bring you closer to the outcomes and goals you are seeking to achieve, you should have identified your preferred response or option.

The key to a good assessment of alternatives is to define the opportunity or threat exactly. Then specify the decision criteria that should influence the selection of alternatives for responding to the problem or opportunity.

Key questions to ask:

- Does one stand out as a clear winner?

- Which alternatives, while highly attractive, are also laden with excessive risk?

- Which alternatives more closely align with strong opportunities?

Related to each potential alternative or solution are risks, opportunities and actions required to bring the solutions to life. These must support the achievement of your goals.

- There are no totally risk-free alternatives. Risk are known uncertainties that will vary by the consequence and their probability of occurrence. Generally known as threats to the achievement of your objectives, risks must be identified and managed to be successful.

- Opportunities are the positive side of risk. They can vary by their strength and their probability of occurrence. Like a glass half full, seize upon the opportunities that present themselves.

- Execution relates to the implementation of your preferred solution, which is chosen based on your decision criteria. Effectively execute your preferred solution. Translate what looks good on paper to achieve success.

Decision certainty is most often difficult to obtain. Not deciding at all, procrastination or hoping-and-praying that a solution would present itself may not be an outcome you are seeking to achieve.

A person who makes a thousand wrong decisions is better off than a person who makes no decisions at all. This is because the person who has made a thousand wrong decisions has ruled out a thousand things that do not work for them.

Speed of decision making and action taking must equal the speed of change

Life is indisputably faster today than it was before. Technology ensures that most of us are continuously plugged in.

The business landscape today has become increasingly complex and fast-paced especially with the Internet of Things and other disruptive technologies. The velocity of risk is the speed or ferocity with which events occur in today’s business environment.

Risk velocity measures how fast an exposure can impact you or an organisation. It is the time that passes between the occurrence of an event and the point at which you first feel its effects.

In an environment where speed is of the essence, the ability to manage risk and uncertainty and decide quickly is paramount.

When decision makers are within their domain of expertise or faced with emergencies, they can make quick decisions by relying on pattern recognition models. Intuitive and deliberative decisions each have their place. A critical decision-making skill is learning to stop and think to choose the appropriate approach.

The rate at which an uncertainty, a risk or an opportunity can impact you or your organisation is an important reason for making timely or quick decisions. The phrase “deciding at the speed of risk” will become normal.

If the speed at which you make decisions and act does not equal (at the minimum) to the speed at which things change around you, then opportunities will be lost, and success will not be at hand.

But when things or circumstances are slow, then you do not need to make decisions quickly. Your decision-making speed is contextual or circumstantial.

A survey by McKinsey showed that decision-making ‘winners’ who made good decisions fast and execute them quickly see higher growth rates or overall returns from their decisions.

Therefore, either categorise your decisions into four McKinsey decision types – big-bet, cross-cutting, ad-hoc and delegated decisions, or use Amazon’s Type 1 irreversible and highly consequential decisions or Type 2 reversible decisions to speed up your decision-making process, where appropriate.

As guidance, Jeff Bezos of Amazon considers 70% certainty to be the cut-off point where it is appropriate to decide. That means acting once you have 70% of the required information, instead of waiting longer. Deciding at 70% certainty and then course-correcting is a lot more effective than waiting for 90% certainty and losing the opportunity.

Executing or implementing your preferred solution

Once your preferred alternative or response has been identified after applying your chosen assessment technique and comparing the assessment results against your pre-defined decision criteria, it is time to implement or execute your preferred solution.

You can have the best strategy or preferred response written on paper, but if you don’t implement or execute the action to bring that preferred solution to life, it is not going to benefit you.

Implementation also shows commitment to action.

Continuously evaluating your decision-making performance

Once you have successfully implemented your preferred solution, it is time to evaluate the degree that your implemented solution meets your decision criteria.

Evaluating your decision-making performance will help you improve your decision-making skills and make better decision in the future. You learn from your successes and failures.

Your decision-making performance is based on:

- The degree your chosen solution meets your decision criteria.

- Whether your actions were implemented effectively within the stated timeframe, capability, capacity and resource constraints.

Meeting the six requirements for making good decisions

In the face of uncertainty – upside or downside, you can only judge the quality of a decision at the time it is being made, not after the outcome becomes known. That means a good decision can have a good or bad outcome.

Therefore, the most fundamental distinction in decision making is that between the quality of the decision and the quality of the outcome.

Given that you can only control the decision but not the long-term outcome in the face of uncertainty, there are six quality requirements for making good decisions according to the book, Decision Quality: Value Creation from Better Business Decisions:

- An appropriate frame – Right frame (What is it that I am deciding?)

- Creative alternatives – Right alternatives (What are my choices?)

- Relevant and reliable information – Right information (What do I need to know?)

- Clear values and trade-offs – Right values (What consequences do I care about?)

- Sound reasoning – Right reasoning (Am I thinking straight about this?)

- Commitment to action – Decision maker (Will I really take action?)

An appropriate frame specifies the problem or opportunity that you are tackling, including what is to be decided.

Along with the frame, three things must be clarified – The creative alternatives define what you can do; relevant and reliable information captures what you know and believe (but cannot control); and values and trade-offs represent what you want and hope to achieve. Together these three form the decision basis.

They are combined using sound reasoning, which guides you to the best choice given what you want (based on your values) and considering what you know (relevant and reliable information). Reasoning helps us understand what you should do, creating clarity of intention. It has the ability to generate conclusions from assumptions or premises.

However, an intention has little practical value. To have a real decision, you must act. Thus, commitment to action must be an integral part of the decision, and decision-making process.

When all six quality requirements are met, you have reached a decision quality (DQ). It is the destination of a high-quality decision. Meeting all six quality decisions are necessary for DQ. If one is not met, then the decision cannot be high quality. The quality of a decision is only as good as its weakest link.

If you make good decisions, there is no place for regret in your thinking. Just continue to make good decisions. Why regret if you made a good decision and the outcome was out of your control?

If you find you are worrying about a decision before making it, transfer your energy to making sure it is the best decision you can make.

Key factors that influence decision making

Experience

Past experiences can impact future decision making. When something positive results from a decision, people are more likely to decide in a similar way, given a similar situation.

On the other hand, people tend to avoid repeating past mistakes, if possible.

Emotions impact our decisions

Several brain structures that are involved in decision making – the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), orbitofrontal cortex and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

When it comes to decision making, our brain does not react in the same way if we are following directions from someone else. There are different patterns of brain activity depending on whether they were told what to do, or if they could freely decide how to act.

An important aspect of the neuroscience of decision making is emotions.

Emotions are created when the brain interprets what is going on around us through our memories, thoughts, and beliefs. This triggers how we feel and behave. All our decisions are influenced by this process in some way.

For example, if you are feeling happy, you might decide to walk home via a sunny park. But if you had been chased by a dog as a child, that same sunny park might trigger feelings of fear. You would take the bus instead.

Different emotions effect decisions in different ways. If you are feeling sad, you might be more willing to settle for things that are not in your favour. For example, not putting yourself forward for promotion, or remaining in an unhealthy relationship.

Sadness can make you more generous. For example, unhappy people are more likely to be in favour of increasing benefits to welfare recipients than angry people, who are lacking in empathy.

If you understand where your emotions come from and start to notice how they impact your thinking and behaviour, then you can practice managing your response. You learn to make better choices.

Escalation of commitment and sunk outcomes

People invest larger amounts of time, money, and effort into a decision to which they feel committed (escalation of commitment) or unrecoverable costs. For example, they will tend to continue to make risky decisions when they feel responsible for the sunk costs, time, money, and effort already spent on a project.

As a result, decision making may at times be influenced by ‘how far in the hole’ the individual feels he or she is. Therefore, people make decisions based on an irrational escalation of commitment.

Skin in the game

When you believe what you decide matters, you are more likely to decide.

For example, people vote when they believe their vote counts. They will vote more readily when they believe their opinion is indicative of the attitudes of the general population, as well as when they have a regard for their own importance in the outcomes.

Environment or context

Subtle factors around you shape your behaviour. At time, you may fail to recognise those influences:

- Want to get people to put a donation for coffee in the honest box? On a shelf above the coffee urn, place a coconut in a certain orientation.

- Want to persuade someone to believe something by giving them an editorial to read? Make sure the font type is clear and attractive. Messy-looking messages are much less persuasive regardless of the message itself.

- That’s not world-shocking, but if the person reads the editorial in a seafood store or on a wharf, its argument may be rejected — if the person is from a culture that uses the expression “fishy” to mean “dubious,” that is.

- Want to be paroled from prison? Try to get a hearing right after lunch. Investigators found that if Israeli judges had just finished a meal, there was a 66 percent chance they would vote for parole.

- Want someone you are just about to meet to find you to be warm and cuddly? Hand them a hot cup of coffee to hold. And don’t by any means make that an iced coffee.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

In isolated contexts, social psychology has uncovered shrouded predictors of judgments and actions.

Many experiments show how modifications of contextual details cause predictable changes in behaviour without subjects realising these factors affected them at all.

Cognitive biases

Decision-making is fraught with biases that could cloud your judgment and decision-making.

Cognitive biases influence people by causing them to over rely or lend more credence to expected observations and previous knowledge, while dismissing information or observations that are perceived as uncertain, without looking at the bigger picture.

While this influence may lead to poor decisions sometimes, the cognitive biases enable individuals to make efficient decisions with assistance of heuristics.

You may misremember bad experiences as good, and vice versa.

You let your emotions turn a rational choice into an irrational one.

You use social cues, even subconsciously, to make choices that you would have otherwise avoided.

This chart, compiled by Business Insider, shows 20 common cognitive biases that could trip up your decision-making.

The field of behavioural economics, led by social psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, has identified a number of cognitive biases that affect decision-making — usually in a negative way.

There is no definitive list of such biases, but Wikipedia lists 124 decision-oriented biases. It is sobering to note all the ways in which human brains distort decision processes. Perhaps, it is a wonder that any good decision can ever be made!

Decision making is a complex process. There are many other factors such as your environment, time-pressure, and your actual and perceived knowledge that can impact the quality of decisions you make.

Being aware that you are usually not making decisions in a vacuum is important in order to start making smarter decisions.

Decision fatigue

Decision-making is tiring.

Picking your clothes, where to eat, what music to listen to, and what to do in your free time all demand your brain to exert that energy daily.

A great deal of research has found that humans have a limited amount of mental energy to devote to making choices. By analysing more than 1,100 decisions over the course of a year, prisoners who appeared in front of judges early in the morning received parole about 70 percent of the time, while those who appeared late in the day were paroled less than 10 percent of the time.

To a fatigued judge, denying parole seems like the easier call not only because it preserves the status quo and eliminates the risk of a parolee going on a crime spree but also because it leaves more options open. Judges retain the option of paroling the prisoner at a future date without sacrificing the option of keeping him securely in prison right now.

Decision fatigue helps explain why ordinarily sensible people get angry at colleagues and families, splurge on clothes, buy junk food at the supermarket and cannot resist the dealer’s offer to rustproof their new car.

No matter how rational and high-minded you try to be, you cannot make decision after decision without paying a biological price. Once you are mentally depleted, you become reluctant to make trade-offs, which involve a particularly advanced and taxing form of decision making.

Your personality

Your personality or personal “style” will inform whether you approach decisions rationally or emotionally, impulsively or cautiously, spontaneously or deliberately. Understanding your personality can help you make better choices and stress less over the decisions that you make.

If you have daring and adventurous components to your personality, you may find that you are quick, even impulsive in making decisions versus your analytic counterpart that may need to contemplate every angle before deciding.

Personality assessments offer a process of self-discovery with very useful applications. The more you know about yourself, the more your options, choices and perspectives increase exponentially!

Self-awareness not only “unblocks” you, but also opens possibilities that might otherwise remain unconscious or unknown to you.

Start by looking at what works for you and what doesn’t. What are the major themes and patterns?

If you continually feel like you’re trying to fit a square peg in a round hole, you’re probably ignoring the needs and uniqueness of your own personality.

If you have the options between two job offers, and one is working from home and the other is in a busy and interactive office place, how do you decide which is right for you?

Knowing something about yourself and your preferences can help.

What makes you indecisive and how to beat it

Making decisions, big or small, is like standing at the crossroads of life. Every decision you make comes with a certain proportion of risk attached to it.

Fear of taking responsibility

At times, you fear making decisions either because you do not want to take ownership of the consequences or you’ve had a discouraging experience in the past.

Either way, you avoid deciding by brushing the problem under the carpet as you do not want to take the blame if something goes wrong.

The way out is to learn to live with the consequences of your decisions – good or bad. Ask yourself, “What’s the worst that can happen?”

Take responsibility for your choices and learn from your experiences. If your decision has led you to move away from close friends, know that you can make new ones.

Choosing a dream job in another city will separate you from your family. Look at the positive side. You are living your dreams. Moreover, you can always meet them on weekends.

When you identify your fear, you are ready with concrete solutions. By doing this you weaken its power to control your decision-making ability and beat indecisiveness.

Having countless choices

Excess of choices can baffle you. They can drive you into decisions that are not in your best interest.

Moreover, asking for too much advice from others will lengthen your list of options and bring you back to square one. So, beware of the paradox of choice.

The way out is to make a list of your choices and write down the pros and cons of each. This simple act of sitting down with a calm mind and evaluating your options makes you understand every facet of the situation.

You get clarity on your objective and figure out the best way to achieve it. Then, you won’t be indecisive anymore.

The call for perfection

If you strive for perfection in everything, chances are you will put off deciding for as long as possible because you fear failure.

The way out is to start small and accept the fact that new challenges will crop up later. Enjoy the journey and learn to take challenges in your stride. Avoid waiting for conditions to be perfect to get started.

Mark Zuckerberg started with a small business objective of connecting college students and faced multiple decision-making issues when he launched Facebook. However, he decided to take some calculated risks, backed by solid groundwork.

Mark approached every problem by asking “Will this help us grow?”

This has helped him plan for contingencies. Facebook now connects the world and is a global phenomenon.

Being a people pleaser

Nothing leads to indecisiveness faster than letting the desire to please others dictate your actions. From choosing a new dress to deciding what to eat, seems like a life-altering choice because you are allowing people’s views to drown your voice.

The way out is to make self-awareness a priority. You cannot make everyone happy. Your friend asks you to pick the cuisine for dinner and you choose Mexican food. Maybe he longed for Italian food? But he asked you. You were honest.

Your opinion is acceptable!

Only you can make decisions that are right for you.

So, focus on your own likes and dislikes.

As a result, that will help you get out of the indecisiveness trap.

The analysis-paralysis issue

Indecisiveness can be the result of overthinking. There will come a time when you feel handicapped about deciding.

Without a doubt, analysis is done with the intention to come up with judicious decisions and strategies. However, over-analysing will worsen your ability to make a prompt decision.

The way out to is to accept the limits of analysing the problem. Understand that over-analysing a situation will not help you in any way.

Take quick action, examine the consequences, learn from mistakes, take corrective measures, leave indecisiveness behind and move on.

Let’s say you desire to pursue a course that will help you gain an edge over your peers at your workplace.

In such a case, fretting over your ability to cope with the additional challenges that will come with pursuing further studies is futile. You will face challenges while managing your home, work, and studies.

Accepting these challenges and overcoming them will make you more confident.

Other considerations when making decisions

Using rhythm to make better decisions

The Pomodoro Technique involves working in 25-minute intervals with five-minute breaks in between.

The core process of the Pomodoro Technique consists of six steps:

- Choose a task you would like to get done – Something big, something small, something you have been putting off for a million years. It doesn’t matter. What matters is that it is something that deserves your full, undivided attention.

- Set the Pomodoro for 25 minutes – Make a small oath to yourself: “I will spend 25 minutes on this task, and I will not interrupt myself.” After all, it’s just 25 minutes.

- Work on the task until the Pomodoro rings – Immerse yourself in the task for the next 25 minutes. If you suddenly realise you have something else you need to do, write the task down on a sheet of paper.

- When the Pomodoro rings, put a checkmark on a paper – Congratulations! You’ve spent an entire, interruption-less Pomodoro on a task.

- Take a short break – Breathe, meditate, grab a cup of coffee, go for a short walk or do something else relaxing (i.e., not work-related). Your brain will thank you later.

- Every 4 pomodoros, take a longer break – Once you’ve completed four pomodoros, you can take a longer break. 20 minutes is good. Or 30 minutes. Your brain will use this time to assimilate new information and rest before the next round of Pomodoros.

Recognise these rhythms to improve our productivity through deep work. You can become aware of how they are affecting you and use that knowledge to make better decisions.

The benefits of the Pomodoro Technique include:

- Enhances focus – This technique requires 25 minutes of complete focus and dedication while executing a task. It also enhances concentration.

- Helps to navigate into difficult tasks – When a single task has been broken down into several small tasks then it seems achievable and manageable. In the long run, it helps delving deep and finalising seemingly difficult tasks.

- Improves your decision making – This method requires proper planning and partitioning of your time. You decide on things that are more important and need majority of your attention and energy. In the long run, this makes your decision making both easier and more effective.

- Reduces the interruptions and distractions – This technique requires dedication, discipline and strong will power. People are habitual in checking their social media handles or looking at their phones for notifications frequently and even while they are working.

- Makes you focused towards your goals – Your goals will be the driving force that will make you follow this technique. You will be able to see that you are already walking determined and undeterred towards the achievement of your long-term goals in life. It is this realisation that shall be the driving force pushing you further into following it for a lifetime.

A brief period of distraction can be good just before deciding

When faced with a difficult decision, it is often suggested to “sleep on it” or take a break from thinking about the decision in order to gain clarity. The Pomodoro Technique enforces this.

Published in the journal “Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience,” the research finds that the brain regions responsible for making decisions continue to be active even when the conscious brain is distracted with a different task. Participants did not have any awareness that their brains were still working on the decision problem while they were engaged in an unrelated task or a difficult distractor task like memorising sequences of numbers.

The key thing to note about the research is that it involved a brief period of distraction — in this case two minutes. A distraction is defined as something that grabs your attention. And this short distraction prevented people from consciously thinking about the decision information.

In another study published in the journal Psychological Science, you may be better able to make a complex decision after a period of simple distraction than a period of conscious focus.

In the study, led by Marlene Abadie of the University of Toulouse, researchers presented participants with a complex problem-solving question. Participants were given either a simple matching game to distract them, a complex distraction, or a quiet period in which to focus and reflect on the problem.

Researchers found that participants who came back to the problem after a simple distraction – like number matching – had a 75 percent chance of giving the right answer. Participants who experienced no distractions whatsoever had a 40 percent chance of answering correctly.

However, the unconscious-thought effect (UTE), which allows people to make better decisions after a period of distraction seems only to apply to simple distractions. Participants given a more complex distraction also had a 40 percent chance of answering correctly.

It was only following a low-demand distraction task that participants chose the best alternative more often and displayed enhanced gist memory for decision-relevant attributes. These findings suggest that the UTE occurs only if cognitive resources are available and that it is accompanied by enhanced organisation of information in memory, as shown by the increase in gist memory.

This is because your brain can process more factors when your conscious self isn’t involved. Your conscious mind has a capacity constraint. It can only think about a couple of features at once.

Your unconscious mind doesn’t have these capacity constraints. It can weigh all relevant information more effectively.

Conscious deliberate decisions are finite

You make dozens of decisions every day – some simple, some more complex.

Some Internet sources estimate that an adult makes about 35,000 conscious decisions each day. People make 226.7 decisions each day on just food alone according to researchers at Cornell University.

In the publication, Science, researchers argue that effective, conscious decision-making requires cognitive resources. Increasingly complex decisions place increasing strain on these limited finite resources.

The quality of your decisions declines as the complexity of decisions increases.

In short, complex decisions overrun your cognitive powers.

Your brain functions in two modes.

- One mode is largely automatic – It makes reactive decisions based on intuition.

- The second mode is deliberate – It makes rational, analytical decisions.

The second mode is finite.

You can only make so many logical decisions per day before the tank is empty. Each of these decisions requires your conscious attention and mental energy.

Therefore, excessive, unimportant mini-decisions waste this finite resource. It takes a toll on your day-to-day wellbeing and decision making.

Early morning can be your best time to make good decisions. Schedule the most attention-rich tasks when you have a fresh and alert mind. Deep work most often occurs in the morning.

The number of decisions you make in a day can get so overwhelming that by the time you get home, you can barely decide what to eat for dinner.